We're Alive (1974)

Our guest writer is Beth Capper, Assistant Professor of Media Studies at the University of Alberta. She has written on media, Marxism, and the politics of social reproduction for Third Text, TDR, GLQ, and Jump Cut, among others. She is also currently at work on a monograph titled Uncommon Reproductions: Feminism, Cinema and the Crises of Capitalism that advances a revisionary history of labor and anti-capitalist critique in post-1970s U.S. cinema through an attention to the politics of social reproduction.

A new digital restoration of We're Alive (1974) screens at the Billy Wilder Theater at the Hammer Museum on Saturday, January 28, 2023 at 7:30 p.m. with the filmmakers and other guest speakers in person. Free admission. Learn more.

We’re Alive (1974), a collaborative film created by the UCLA Women’s Film Workshop and the Video Workshop of the California Institution for Women (CIW), is a riotous, tender, and politically incisive exploration of women’s incarceration. Made in 1974, against the backdrop of conservative and liberal law-and-order agendas that significantly expanded carceral power in California, the film indexes some of the political-economic conditions that led to the rise of mass incarceration in the 1980s.1 In particular, We’re Alive shows how the growing incarceration of Black women, women of color, and poor women was—and continues to be—tied to the state’s criminalization and decimation of the social supports that enable women and their broader communities to reproduce themselves. Upon its release, the film circulated in feminist film programs and activist spaces, often as part of fundraising events for the Santa Cruz Women’s Prison Project, an abolitionist group that ran prison education workshops in CIW during the same period.2 As described in a 1975 issue of the journal Off Our Backs, We’re Alive is a film that was “universally loved” by audiences.3 However, like many feminist documentaries of the 1970s, it has since fallen out of circulation. The UCLA Film & Television Archive’s digital restoration of We’re Alive not only introduces new audiences to this remarkable film, but also makes the film’s political analysis of the carceral state newly available. This is especially crucial during a moment of widespread public engagement with abolitionist political frameworks and popular criticism of the prison industrial complex.

While some recent documentaries (such as The Prison in Twelve Landscapes and 13th) have offered political (albeit frictional) analyses of the structural foundations of the carceral state, critics have pointed out that prison documentaries in general tend to treat the prison as an exceptional space disconnected from the activities and institutions central to the lives of non-incarcerated people.4 This has the effect of obscuring the conditions that produce prisons, as well as the suffusion of carceral power across the social landscape. We’re Alive, by contrast, suggests that the ideological and physical separation of the prison from other political struggles is a central strategy through which the carceral state reproduces itself. To counter this strategy, the film works to reveal how incarcerated women’s struggles are intimately entwined with a range of other anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and feminist struggles.

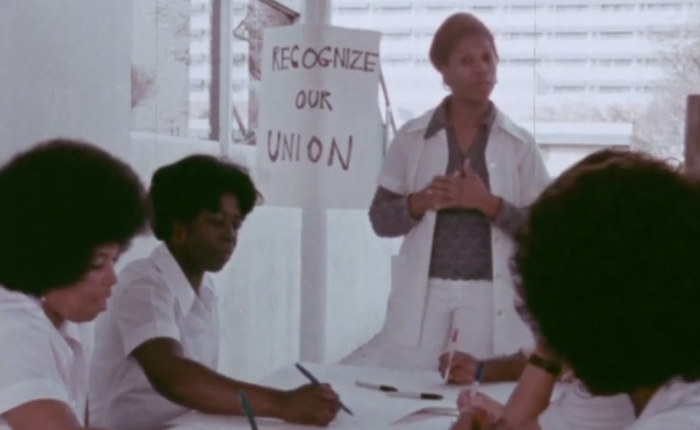

We’re Alive represents feminist collectivity and dialogue—including those convened by the film’s own production and exhibition—as a means for overcoming carceral logics of enclosure and separation. This is most pronounced in the montages that bookend the film, both of which take place outside the walls of CIW. We’re Alive’s opening montage weaves together images of women performing various forms of racially gendered labor, from mothering to waged domestic work to stripping, as well as sites associated with the reproduction of both gender and the family. The soundtrack that accompanies this montage consists of a non-diegetic folk song, which we later learn was composed and performed by a woman incarcerated at CIW. The song’s lyrics, which narrate an incarcerated woman’s struggle to “rise” in the morning, evoke a sense of resignation and isolation that saturates the images of gendered socialization and exploitation that comprise the montage. This communicates the depoliticizing effects of socially segmenting women’s lives, labors, and struggles. However, this segmentation is undone in the film’s closing montage, which collates scenes of feminist protest and organizing for reproductive and economic justice, including scenes of a demonstration against the forced sterilization of women of color, and of Black household workers forming a union. Again, these scenes are scored by a folk song, but whereas the opening song voiced feelings of resignation, the song that concludes the film is a protest song that tells of incarcerated women’s struggles against the prison system. Through the interplay between sound and image in these sequences, We’re Alive suggests the importance of resisting the social divisions produced by the carceral capitalist order.

With the exception of these two montages, the majority of We’re Alive takes place inside of CIW, and is entirely composed of interviews with incarcerated women speaking directly to the camera and sequences of a talking circle, where incarcerated women address one another. These women’s stories highlight how the gendered and racialized logics of carceral capitalism contour their lives at the welfare office, in the neighborhood, and the healthcare system. The political analyses contained within these stories is accentuated by occasional intertitles, which group the women’s comments that address a particular issue, such as gendered unemployment. But more crucially they demonstrate that the women’s experiences exceed individual barriers and defy reformist solutions. In one sequence, for example, incarcerated women testify that the dearth of vocational training in prison illustrates the lie of prison “rehabilitation.” The intertitle that immediately follows these scenes then reads: “If prisons offered adequate vocational training, over 2 million ‘rehabilitated’ prisoners [...] would be released to a job market which already (November 1974) has 5,950,000 unemployed.” This sequence illustrates that a prison with better programs is no solution to the structural conditions, such as mass unemployment, that the women are forced to navigate; indeed, such conditions are shown to be constitutive features of carceral capitalism.

As the women’s stories accumulate throughout We’re Alive, they work to remap the relations between the prison and its “outsides.” As one incarcerated woman suggests towards the end of the film, these dialogic exchanges, made possible by prison education workshops such as the one that produced We’re Alive, disclose carceral power as a social relation that connects multiple spaces and sites. “What they [the workshops] do is they give you a tee-total picture of the whole United States, of the whole fucking system really. You know, how it is, how it affects us, the things that it does to put money in this one's pocket, and consequently taking away something from me or somebody else like me.” While, earlier, We’re Alive underscores the limits of reformist programming in prisons, this moment more hopefully signals that such programs might be covertly redeployed on behalf of anti-carceral and non-reformist agendas, galvanizing a shared analysis of the prison system and new relations of solidarity.

Footnotes

1 During the moment that We’re Alive was being filmed, for instance, two recessions, one national and the other global, had nearly doubled unemployment in the state of California. See Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007) for a fuller account of the rise of the prison industrial complex in California.

2 Karlene Faith, Unruly Women: The Politics of Confinement and Resistance (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2011), p. 411.

3 f.m. “iris - movie marathon,” Off Our Backs vol. 5, no. 8 (September-October 1975), p. 11.

4 Some analyses of the carceral state advanced by recent documentaries are not without their critics. See, for example, Dan Berger’s critical appraisal of Ava DuVernay’s 13th. For critiques of the formal, rhetorical, and political conventions of the U.S. prison documentary, see Michelle Brown, “Penal Spectatorship and the Culture of Punishment,” in Why Prison?, edited by David Scott (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013) and Brett Story, “Against a ‘Humanizing’ Prison Cinema: The Prison in Twelve Landscapes and the Politics of Abolition,” in Routledge International Handbook of Visual Criminology (London and New York: Routledge, 2017).

Watch the film:

Watch the post-screening conversation:

Additional reading:

Blog: “We're Alive”: The State as Great Big-armed Mother

Blog: Interview: “We're Alive” and Experiences of Incarceration at CIW

UCLA Magazine: The Second Life of ‘We’re Alive’

UCLA Newsroom: Injustice remains: 48-year-old women’s prison documentary shows how little has changed

< Back to the Archive Blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation