I wrote my first blog of the year 2016 about This is Cinerama, and now coincidentally I’m posting my last blog of the calendar year on The Best of Cinerama (1962), which recently played at Hollywood’s Cinerama Dome in a restored digital version. That film is also now available for the first time on Blu-ray/DVD through Flicker Alley, as are the other six Cinerama features, This is Cinerama (1952), Cinerama Holiday (1955), Seven Wonders of the World (1956), Search for Paradise (1957), South Seas Adventure (1958), Cinerama’s Russian Adventure (1966), The Voyage of the Christian Radich (1958), as well as the similar Cinemiracle film, Louis de Rochemont’s Windjammer (1958). All seven Cinerama films were digitized and restored utilizing Dave Strohmaier’s Smilebox technology, which simulates the super-wide screen and makes it compatible with your home viewing device.

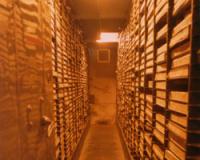

When I arrived at the Cinerama Dome on Sunset Blvd. in Hollywood in early December, I was met by Harrison Engle, Dave Strohmeier and Randy Glitsch, the team responsible for digitally restoring the Cinerama films. Dave immediately invited me to tour the old Cinerama Dome projection booth, which I had never seen. Obviously, the Cinerama Dome relies today on a DCP digital projection system, and so The Best of Cinerama was projected from the center projector portal, but with an especially calibrated version of SmileBox to match the dimensions of the Dome’s screen. But the old Cinerama 35mm projectors are also still up in the booth, although a bit dusty and surrounded by theater clutter. The booth itself circles around the back of the theater in a 45-degree arc, which perhaps makes it the widest booth on the planet. The three 35mm projectors, placed at the extreme left and right, and in the center, are still operational, with the left and right projector images actually crossing each other, while the center projector throws its image straight at the screen. Ironically, no three-projector films were ever shown at the Dome, because the Dome opened in February 1963 with the new single 70mm projector process for the premiere It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. Given the lack of projectable Cinerama prints, it is unlikely we’ll see any more 35mm films screened in that format.

The Best of Cinerama, like all the now released Cinerama films, is a unique cultural experience, a time capsule of mores, morality and middle American ideology in the mid-20th century. Obviously, what the widescreen format did best was forward camera movement, and the opening sequences of jets and a classic rollercoaster ride provide plenty of thrills, as do later a bob-sled and ski ride in St. Moritz and the rickety, runaway Darjeeling railroad sequence, thanks to the intense kinetic movement in the viewer’s peripheral vision. Much of the remaining travelogue footage is held in panoramic long shots, presenting either flyovers of famous sights of the world or static shots of rituals and dances emphasizing the ethnic other. Thus, while Hindu rituals at Benares are characterized as a strange mysticism, a celebration at St. Peter’s with Pope Pius XII, as well as the films’ apotheosis, aerial shots of Bethlehem and the sites of the crucifixion and ascension of Christ, are presented as naturalized facts.

A few days later at home, I watched the DVD of Cinerama’s Russian Adventure, certainly the wackiest of the Cinerama films. That film is actually a compilation of scenes from the Soviet version of Cinerama, called Kinopanorama. Invented in 1956-57 by the Soviet inventor Evsei Mikhailovich Goldovskii, the Russian camera was apparently much smaller and more mobile, allowing for some truly amazing footage. The film opens with a troika race in the snow and later we get a reindeer race, both filmed at break-neck speed, but it is the film’s mise en scene, moving people and things right up into near close-ups, which differentiates it from the long shot Cinerama films. The camera at times seems to be completely unhinged, as when it is suspended from a circus trapeze or twirling 360 degrees at rapid speeds to follow horses and their riders in a small ring.

Eight travelogues were eventually produced in the Kinopanorama process, the first of which, Great is My Country (Roman Karmen, 1958), actually screened in New York in 1958. Most surprisingly, the Russian Adventure eschews even a single ideological remark. Bing Crosby’s folksy narration presents Soviet Russia as virtually identical to the United States only bigger; not one word about Communism or the Cold War, just happy peasants in ethnic dress and the Bolshoi Ballet as a signifier of the country’s love for the arts. However, as pure spectacle, the Cinerama films deserve our attention.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation