At 1:30pm, UCLA Assistant Professor Allyson Nadia Field introduced the second panel of the day at the November 12th all-day symposium for the UCLA Film & Television Archive’s Fall 2011 program, “L.A. Rebellion: Creating a New Black Cinema.” Getting underway quickly, Professor Field introduced the first of three panelists speaking that hour. Daniel Widener, Associate Professor in the Department of History at UC San Diego, took to the podium to present his talk on how the films of the L.A. Rebellion helped to form an organic connection to liberation movements abroad.

Referencing goals he had in writing his 2010 book, Black Arts West: Culture and Struggle in Post War Los Angeles, Professor Widener stated that he was trying to get people to have a broader sense of the Black Arts movement. The movement was “an effort to produce a liberation art,” even if the films themselves don't thematically broach what would typically be considered liberation oriented content.

Professor Widener presented the cement of his argument when speaking of several “revolutionary things” that the L.A. Rebellion films did. Perhaps for the first time historically, these films challenged genre. The filmmakers of the L.A. Rebellion group dared to create something original in the face of the pressure to conform. The second “revolutionary thing” Widener referenced was that the films take Black people as subjects. More importantly, they are subjects of their own histories. As he noted, “These are people that have the ability to solve problems that they didn’t even create.” Pointing to the untraditional role that music plays, these films also evoke an understanding of their time on their own terms. Finally, Widener, including himself in the body of Black subjects that the films represent, spoke to the films’ ability to “point to our own underdevelopment as a people,” and supplemented it with another unique aspect of this body of work, that the films also “point to the failure of the institutions around us.”

“We are living in a time of repression... a repression of our memory. These films and this symposium provided a critical entry point to awareness of this repression.”

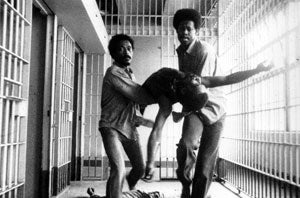

Morgan Woolsey, the second presenter, discussed the ways in which Larry Clark’s Passing Through (1977) communicated meaning through sound and music. Building from the idea that music has been tied to meaning making in film since the introduction of sound, Woolsey also proposed that music could be used in film to deconstruct a character’s personal narrative. She showed several key scenes from the film, each visually and thematically related through the connections between jazz music, Warmack, and Poppa Harris.

In one pivotal scene, one that illuminates Cauleen Smith’s argument (in the third paper, discussed below) about Clark’s use of silhouette as a liminal space where thought and experience intersect, Warmack plays his saxophone at the beach, caught between light and darkness, the musical phrases emerging from his saxophone overlapping one another in a melodious jazz tune. Woolsey likened the overlapping phrases to the waves surrounding Warmack, crashing against the beach in a rhythmic cycle. The overlapping notes that began as diagetic sound and morphed to an exteriority beyond the film, deconstructs an emotional moment for Warmack that Woolsey argues lends itself to the reading that Warmack is trapped by the notes ingrained in him by Poppa Harris, but has not yet made them his own. This cyclical relationship with his past and Poppa Harris emotionally emboldens him, but simultaneously limits Warmack’s progression towards finding himself and making music specific to his own experiences, not just those passed down by his mentor and grandfather. Warmack is able to connect to his past through music, or what Woolsey describes as “a loving pedagogy that transcends time and distance,” but is caught in a cycle of remembrance that stifles his own personal progression.

In such a scene, it becomes clear that music does have the power to symbolically deconstruct and underscore the interiority of Warmack’s personal struggles. Unlike the manipulative powers of music as it is often used in Hollywood films, for Passing Through,“musical movement works in tandem with the physical and emotional movement of its characters.” Warmack’s saxophone playing emotionally reflects Warmack's complicated subjectivity, and works to destabilize that subjectivity throughout the film as Warmack comes into his own by coming to terms with his past and embracing his future.

Cauleen Smith, the last presenter on the panel, gave an excellent and engaging analysis of light and darkness as it relates to gender in Passing Through. Smith pointed out the positive attributes expressed through the dark background in the film, and contrasted it with those of tension and uncertainty when white colors are allowed to dominate the film. For example, when Warmack is playing the saxophone using techniques taught by his grandfather the film is a deep inky black, but there is almost over exposed brightness present when Warmack is in a place of tension. She observes that dark colors in the film are associated with warmth, comfort, and family while white is associated with danger and discomfort. Sepia tones are used in the film to portray liminal spaces when Warmack is in a place of growth. Smith further notes that women primarily exist in dark or white spaces in the film, but when a woman exists in the sepia liminal spaces, chaos results. For Smith, the chaos that ensues when a woman is placed in a space of growth is emblematic of the absence of women portrayed as complete beings that are capable of existing in or lending meaning to multiple spaces. For Smith, Larry Clark’s inability to portray women within multiple color schemes represents filmmakers’ inability to portray women as complex characters who exist alongside men in intricate modes of human and social development.

Smith also spent time to discuss the role jazz played in the film and the overarching presence of jazz as its own character in Passing Through. The long shot in the beginning of the film which shows Horace Tapscott’s hands as he plays the piano, then overlays images of his hands, the piano, and lines of sound in the music. For Smith, this filmic technique speaks to the ability of African American filmmakers to represent themselves and their culture in ways Hollywood could never imagine, imitate, or appreciate. That mainstream audiences of any race never saw Passing Through and many other films in the L.A. Rebellion, explains the dearth of meaningful, complex, diverse films produced by Hollywood today.

—Jeff McCluskey, Rachel Wilson and Dalena Hunter

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation