In a 2010 interview conducted for the L.A. Rebellion series, Haile Gerima explained that the concept for Hour Glass (1971) arose out the political ferment and social activism at UCLA during the period. Civil rights struggles, antiwar protests and Third World revolutions played out at UCLA, fuelling the intellectual and creative environment and Gerima’s own creative and intellectual production. Hour Glass gives expression to the ways in which the political coalesces with the personal and psychical in its haunting dream sequence in which the protagonist comes to political consciousness.

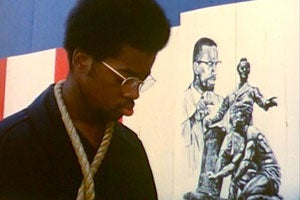

At the Q&A after the Sunday screening of Hour Glass and Ashes and Embers (1982), Gerima described the dream as a moment in which “a boy is trying to find his hero and having them snatched away.” The film’s main character dreams that a young Black boy lies on a bed covered by sheets, each with his heroes’ likenesses silkscreened on them: Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Angela Davis. Audio recordings of their most memorable speeches play over the images. As he pulls each sheet over himself – the first with Malcolm X’s likeness, the second with King’s – a woman in white tears the sheets away and tacks them on the wall. As she does so, their speeches are interrupted by shocked screams, aurally marking their assassinations. When the woman tries to tear away the sheet with Davis’ image the boy fights back furiously, pulling the sheet around him –reflecting that unlike Malcolm X and King, Davis survives and will continue her social activism. The dream is an “awakening,” a space where the protagonist’s troubled thoughts and developing political awareness are given form and structure, enabling him to move forward into an enigmatic but more fulfilling future.

Following Hour Glass, Haile Gerima’s self consciously subversive 1982 film Ashes and Embers played to a quietly riveted audience. At the opening of the film, Gerima’s informed approach to filmmaking draws attention to two young Black males as they are arrested without cause while driving down Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood. In contrast to an established filmic approach, the camerawork focuses on the young men, with a slow motion shot of their faces, both of them on their knees, while faceless white police officers hold them at gunpoint and handcuff them. By giving a face to the arrestees in this scene, Gerima introduces audiences to the table turning tactics he will use to tell his story of a young Black Vietnam veteran, Nay Charles, and his struggles to cope with a war that is still raging within him, eight years after the fighting has ceased.

Calling out Hollywood’s stereotypes directly in the narrative of Ashes & Embers exhibits Gerima’s finely tuned postmodern awareness. The main character’s mockery of a well-known piece of dialog from Frances Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979) serves to parallel the struggle of Black people in Hollywood with the struggles of a veteran trying to make sense of the war in Vietnam. The ironic reference to the Coppola film is well executed, and by reminding the audience of that canonical Vietnam War film, Gerima easily builds a case for his own subversive cinema as one of the more poignant works ever to examine the psychological trauma of war.

Gerima delves deeper into his thoughts about the war in the article, “Thoughts and Concepts: The Making of Ashes and Embers,” published in Black American Literature Forum in 1991. The war in Vietnam never ended for Nay Charles, as was probably the same for anyone who fought. His experience constantly haunts him as he tries desperately to find someone to whom he can relate. And while most Vietnam War vets felt alienated upon their return home (a home where many people did not support the war in which they just fought), Nay must also return to a place that had already alienated him because of his race.

As the years pass, it isn’t the violence and bloodshed that take the main toll on Nay Charles’ psyche; it is the innocent Vietnamese that begin to flood his memories. Initially, Nay identified himself as part of the conquering group and the civilian Vietnamese as non-existent. In Vietnam he was able to bully these people without any qualms because as an American soldier he had the power to do so. In America, though, he is no longer in a position of power and must succumb to being a second-class citizen. He is given no praise or acknowledgement for his time at war and is expected to just live with his problems. Nay Charles begins to associate himself with these “non-existent” people; Gerima states that “the connection Nay Charles comes to make with the plight of the Vietnamese people is the most significant evolutionary process he has entered into.”

"...the role of women and family relations have many important appearances throughout the story that are vital in understanding Haile Gerima’s work."

While the political discussion of African Americans serving in the Vietnam war is obviously one of the most predominant in Ashes & Embers, the role of women and family relations have many important appearances throughout the story that are vital in understanding Haile Gerima’s work. During the Q&A after the screening, Gerima elaborated on the importance of his grandmother’s oral storytelling tradition that he participated in when he was younger. He includes depictions of a similar sense of story and communication with the younger generation listening to the matriarch in Ashes & Embers as they are all gathered around a fire. In the film, this grandmother figure does not come without tension, however, and while she provides a link to safety and security and the past for the veteran Nay Charles, she also praises him for actions for which he is not proud. Nay Charles is upset at those who cannot understand what he has gone through as he slowly tries to cope with his trauma. It seems that what he truly longs for is a less complicated divide between himself and the African American women around him that he wishes to be understood by, and be able to stand unified with instead.

At the Q&A, Gerima also discussed the way in which he views his work as a continuous flow, how one project creates space for and precipitates the next. He echoes this sentiment in an oral history conducted as part of the L.A. Rebellion project, noting that, for him, Ashes & Embers very clearly leads to Sankofa, his groundbreaking 1993 feature about the history of slavery told the perspective of the enslaved.

In Ashes & Embers, Gerima guides us through the process of change as it unfolds for the central character, Nay Charles, by very carefully positioning him in a number of settings—Hollywood, Vietnam, Washington, DC and his grandmother’s country home—and orchestrating interactions with strong figures from various backgrounds and generations—his grandmother, Jim the TV repairman, Liza Jane the activist and Randolph the actor. While all of the characters serve a very deliberate role in the film, Nay Charles’ grandmother is particularly intriguing in when considered in relation to Sankofa: she is firmly grounded in the history of struggle, and, as Gerima notes in “Thoughts and Concepts,” “she embodies history, time, and space.” Sankofa, which evidences Gerima’s continued interest in the history of struggle among Africans and African Americans, can be seen as part of the L.A. Rebellion program on November 19th along with Julie Dash’s Diary of an African Nun (1977).

—Karrmen Crey, Jeff McCluskey, Jessica Hokanson, Laura Paul and Alice Royer

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation

Comments