Pictured, clockwise: Jerovi, Fireworks, Desert Hearts, Tongues Untied, Paris is Burning, Parting Glances

Guest writer Ernest Hardy is a film critic, professor and author, and has a yet-untitled collection of short stories being published by Writ Large later this year. In this essay, he highlights some of the pathbreaking LGBTQ+ films and filmmakers featured in Pioneers of Queer Cinema, opening February 18 at the Billy Wilder Theater at the Hammer Museum.

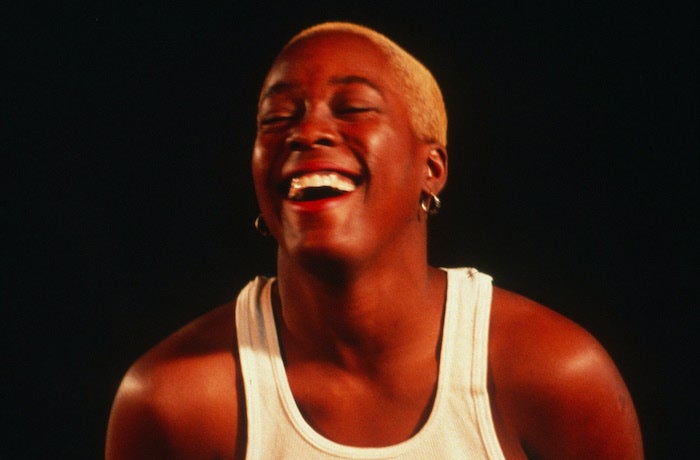

In a 2016 interview with IndieWire, writer/director Cheryl Dunye notes that when she and her filmmaking crew were making the 1996 queer classic The Watermelon Woman, “We didn’t do it thinking we were making something that would last. It was a handmade, D.I.Y., micro-budget feature film. It got a lot of attention. But when you’re young and poor, you don’t imagine you’re making something that’s important for the future. That’s not what’s motivating you.”

What’s driven most queer filmmakers who’ve made pointedly queer film for more than 60 years now hasn’t been the quest for fame or fortune (those weren’t really even options), or even the idea of making foundational and “important” work. It was simply the desire to bring into cinematic existence something of the world as they saw, lived, dreamed, and quite often defied it. Gay & lesbian and queer filmmakers (the terms aren’t necessarily synonymous or interchangeable) have historically been both custodians and makers of history, all at once. That so many of them have fallen through the cracks of history is both ironic—and not.

(“Queer” is used in this essay as many gay, lesbian, trans, and non-binary people have used it for over three decades now—as a word reclaimed in order to defang it, to reconfigure and recast it as a term of empowerment. That said, it’s also understood that many LGBTI elders recoil from the word and do not believe it can be defanged or reclaimed, and I’m very sympathetic to their stance. I also use the word to make the distinction between the conservative, even reactionary, wing of the LGBTI community, and those whose politics most definitely do not tilt toward the right.)

Cheryl Dunye

Pioneers of Queer Cinema is an attempt to recover some American queer films that are now little-known, and many rarely ever seen at all, and put them in conversation with a relative handful of works now deemed classics—with the latter group ranging from Kenneth Anger’s short Fireworks (1947) to some of the heady ‘90s fare that made up the movement film scholar and historian B. Ruby Rich dubbed “New Queer Cinema” in 1992. These are the building blocks that made possible Pose and the slew of queer characters and storylines on TV and across streaming platforms; that paved the way for Todd Haynes’ Carol (2015) and Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight (2016). The shorts and feature films in this program, both narrative and documentary, are just a sliver of the works that were at the forefront of slowly shifting perceptions of and conversations about the queer community, for both queer and non-queer audiences alike.

One of the most volatile topics of conversation in mainstream (and even some queer) discourse about queerness is almost anything to do with queer youth. The recurring media/social media uproar, for instance, over basketball player Dwyane Wade and actress Gabrielle Union’s public displays of love for and acceptance of their trans daughter Zaya reveals not only ongoing public confusion over the vast difference between gender identity and sexuality, but hostility to the fact that many queer people know in childhood that they are somehow “different” from prescriptive dictates of gender and sexuality. Children, especially queer children, are underestimated every day. Many are able to glean from a young age what it means and might cost to be a boy, to be a girl, to not be the one you’re assigned or assumed to be, to know if societal definitions and expectations of sex (genitalia) and/or gender align or not with who you know you are. Three of the films in Pioneers illustrate something of what it means for gay and lesbian children to grapple with their difference while figuring out how to navigate the world. Crucially, all three films—Todd Haynes’ Dottie Gets Spanked (1993), Su Friedrich’s Hide and Seek (1996), Peggy Rajski’s Trevor (1994)—show how pop culture becomes an invaluable tool for kids to figure it out.

Hide and Seek

In Dottie Gets Spanked, young Steven is obsessed with TV character Dottie (modeled on Lucille Ball’s Lucy from I Love Lucy), finding subversion and ingenuity in her outlandish antics, but also an example of resilience when things blow up in your face. As the boy comes up against disdain at home (his suspicious, disapproving dad) and at school, his fantasies become the place in which he not only has power, but wields it with the cruelty he experiences in real life. The film is especially brave laying out how, in the interplay between lived experiences and fantasy, seeds are planted for the ways in which the boy’s adult sexuality might play out. In Hide and Seek, Friedrich wittily blends documentary interviews with adult lesbians and snippets from archival educational films to sketch in the budding lesbianism of 12-year-old Lou. The film kicks off with one woman’s engrossing anecdote about youthful sexual experimentation in which the TV show The Monkees plays a big part. In this context, the sitcom’s ear worm theme song becomes a trenchant anthem of queer rebellion and difference. And the title character in Trevor, like countless gay boys around the world for nearly six decades, worships Diana Ross as his avatar of fierceness and resilience. The role of the diva in shaping and holding so many queer men’s lives has become something of a punchline, but Rajski, with a firm sense of humor in play, captures the poignancy, even urgency, in the heroine worship.

“Capitalism and its perverse relationship to networking and exposure have put a damper on all the ways we can be artists in community together.” —Alexandra Juhasz, one of the producers of The Watermelon Woman.

For a long time, queer film was (obviously) an artifact of the margin. And while it’s true that in many ways this was simply due to large-scale homophobia of the past, it is also worth remembering that a lot of queer filmmakers, especially many of those whose work is in this program, weren’t simply excluded from the mainstream by outside forces, but by their own aesthetic and political concerns. They simply weren’t interested in the kinds of images and narratives that might secure a place in heart and hearth of middle-America. Nowadays, the rallying cry for diversity and representation is sold as the radical, progressive agenda, but underneath the buzzwords there is often a push toward toothless edginess, a politics of conformity often draped in the drag of the alternative or avant-garde, in the pursuit of celebrity and mass appeal; safety.

Blue Diary

Always on Sunday (1962), directed by the filmmaking collective The Gay Girls Riding Club, thumbs its nose at safety and conformity. The short film positively revels in queer culture’s outsider tropes and figures through an air of levity, through tongue-in-cheek knowingness. These are not the homos you bring home to meet mom and dad. Set in a hustler bar full of men clad in often haphazard drag, with everyone drinking, dancing, pulling scams, and being gleefully amoral, Always ends with a sly wink at longstanding myths surrounding Navy men. Jenni Olson’s lovely, meditative Blue Diary (1998) swims in tropes of another type: the lesbian who falls for the straight girl when the latter is just out for an adventure. As a pause-laden voiceover recounts an ill-fated hookup, Olson’s camera matches the rhythm of the speaker while capturing long shots of busy intersections, images of desolate alleyways, and sidewalks absent inhabitants, pulling the viewer into a trance-like state as we digest the words. Kenneth Anger’s landmark Fireworks (1947) retains its bite as an exploration of the relationship between sex, desire, and violence as they fuse and spark the homoerotic current. Viewers also get to track lineage and influence, as Anger’s work was hugely influential on so many queer filmmakers who came later, particularly during the New Queer Cinema era—with the work of Todd Haynes as just one example.

A personal highlight of the program is Nikolai Ursin’s student short film Behind Every Good Man (1967), a docu-fictional look at a day in the life of a Black trans woman in Los Angeles. The ahead-of-its-time film shrewdly mines the tension of how precarious moving through the world can be (both then and now) for Black trans women, but does so without simply serving us clichés and tragedy. Our heroine window shops downtown, indulges a flirtation (or is that a fantasy?), and dances to a deep album cut by The Supremes, but is never defeated, never an object of pity. Still, Ursin, getting at the emotional undertow of pop songs that often score queer life (again showing the power and importance of the pop diva), has the viewer distill deeper meaning from Dionne Warwick’s 1964 hit, “Reach Out for Me” as it plays beneath our heroine’s arm-in-arm stroll with her new beau.

When you go through a day

And the things that people say

They make you feel so small

They make you feel that

Your heart will just never stop aching

And when you just can’t accept

The abuse you are taking

Darlin’ reach out for me…

Behind Every Good Man

The homophobia of the past U.S. presidential administration, as well as the rise in global fascism, racism, homophobia and transphobia, make this a terrifying, even paralyzing moment in which to live, for many. One goal of this program is to show us how to think and create—and thus how to live, how to communicate with and care for one another—under times of daunting, growing oppression and repression. Some tools for that are found in the resourcefulness and talent of the gathered filmmakers, and in the work itself, which doesn’t just imagine and capture queer lives, but also provides critiques on the larger systems (patriarchy, white supremacy, capitalism) and their tools (homophobia, racism, transphobia, classism) that structured and continue to structure daily life in America.

Peep the reason Desert Hearts’ prim, repressed Professor Vivian Bell (a career-high performance by the great Helen Shaver) has to take up residence in Reno in the first place, and we get a sharp look at just how patriarchy once structured the law against women in matters of marriage and divorce. Director Donna Deitch’s exquisite 1985 film (from a script by Natalie Cooper) is the story of a middle-aged woman’s coming-of-age, discovering her sexuality and falling in love with a magnetic soft-butch (Patricia Charbonneau, devouring the screen) in a film that gives us familiar tropes and then explodes them.

Bill Sherwood’s Parting Glances (1986) and Gregg Araki’s The Living End (1992) eschew the milquetoast sentimentality of so many AIDS-themed films to tap into the very specific ways queer people once, out of both love and necessity, bonded and cared for one another. Crucially, both films also tap into the anger that not only sparked and fed the politics of so many queer people (and allies) living with, battling, and organizing/ACTing UP around AIDS in the ‘80s and ‘90s, but also became part of the life force itself for many. Each film in its own way complicated the ways people living with AIDS were depicted, and in doing so also complicated the act of eulogizing people who died from complications of AIDS. What neither film lets us forget is the enormous canvas of hostility and bigotry from both the U.S. government and a depressingly large segment of its citizens against which battles against AIDS were fought.

Desert Hearts

Cheryl Dunye’s genre-bending The Watermelon Woman (part mockumentary, part fiction narrative) not only illustrates how difficult it can be for queer people—especially queer BIPOC—to find themselves in history, it also describes the need to sometimes create the history you seek. The film, which deftly juggles tones and moods, also offers layers of other biting political commentary, notably in the scene in which the character Cheryl (played by Dunye), after being misidentified as a male and accused of theft by antagonistic cops, is falsely arrested.

Rob Epstein’s 1984 documentary The Times of Harvey Milk is a landmark work of historical preservation, documenting the political rise and immeasurable significance of the late Harvey Milk as a political and cultural figure. Epstein, part of the Mariposa Film Group that made the 1997 documentary, Word is Out: Stories of Some of Our Lives, marks one of the first times such a large cross-section of queer folk spoke openly and unabashedly on what it was (is) to be queer in America.

Marlon Riggs’ groundbreaking 1989 documentary Tongues Untied and Jennie Livingston’s 1990 Paris is Burning are cultural bibles of Black queerness (and, in the case of Paris, Black and Latino queerness) that have become mined by pop culture for humor, lingo, and attitude, but whose insightful commentaries and critiques have often been dumbed down or simply overlooked—especially in the case of Paris. And while many Black scholars and cultural critics, including bell hooks, have taken Paris to task for its missteps and shortcomings (e.g., the way it handles the backstories of its collective figures leans hard into tragedy and ignores the narratives that contradict that tack), it—like Tongues Untied—demands to be seriously engaged for documenting queer life that has simultaneously reshaped American culture, and yet remains undervalued—one of the paradoxes of Blackness in America, period.

Paris is Burning

Space constraints don’t allow for every film in the program to be mentioned here, though they all warrant time and consideration. Each one was a stepping stone as queer filmmakers slowly crawled out of the shadows and margins toward selfdefined visibility and agency—agency as artists and citizens. And self-defined visibility is a critical distinction to make. Queer people have long had a kind of visibility as monsters, freaks, cautionary tales, with the staff wielded as a threat in order to keep the larger social herd marching in lockstep. Film was and is a way to take pen in hand and rewrite definitions. Fueling the creative impulses at the root of the films curated for this program are rage, anger, and anguish, yes. But there is also humor, wit, playfulness, irreverence, eroticism, and sensuality. There is vision. When we watch this work, we have to utilize several critical modes at once, making allowances not only for the limitations of the filmmaking technology of the day (limitations often molded into aesthetics and innovations that still seem fresh and timeless) but for politics that were sometimes still evolving. (Though it should be noted that the politics and aesthetics of a lot of “post-marriage rights” queerness have a timidity at distinct odds with the terms and notions of freedom and liberation that once fueled so much of the queer rights movement and so much queer art, and that can be seen in many of the films in Pioneers.)

The value of this program isn’t simply in the way it allows us to see how far we (queer people and culture; larger mainstream/non-queer culture) have come, or even to celebrate past heroes and heroines of cinema and their groundbreaking cultural production—although that is certainly part of this program’s purpose. But it’s also to keep the queer imagination limber and expansive, to celebrate (and reinvigorate) queer aesthetics that aren’t simply about easily digestible content and marketable brands, or claiming a seat at the table of the status quo. It’s to remind us to think beyond the table, beyond assimilation and its handmaidens (celebrity, wealth)… just to think, period. But just as important as all that is the fact that the films curated for this program are simply good films, beyond conversations that might get weighed down by theory, or analysis that so deeply emphasizes political import that the films themselves are made medicinal—“good for you”—rather than being works that inspire, move, engage, and delight as film.

—Ernest Hardy

< Back to the Archive Blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation