Strange Illusion (1945)

During the 1930s and '40s, dozens of small “Poverty Row” film studios operated in the shadow of Paramount, MGM, Warner Bros. and other major players. UCLA Film & Television Archive has been committed to collecting and preserving Poverty Row works, which are often overlooked and neglected but constitute a significant part of American film history. Six restorations will screen in Down and Dirty in Gower Gulch, a series hosted by Raleigh Studios in Hollywood, opening October 27 with a fundraising gala for the Archive's preservation efforts.

Here's Head of Preservation Scott MacQueen on the legacy of Poverty Row and what the Archive is doing to save it:

What was “Poverty Row”?

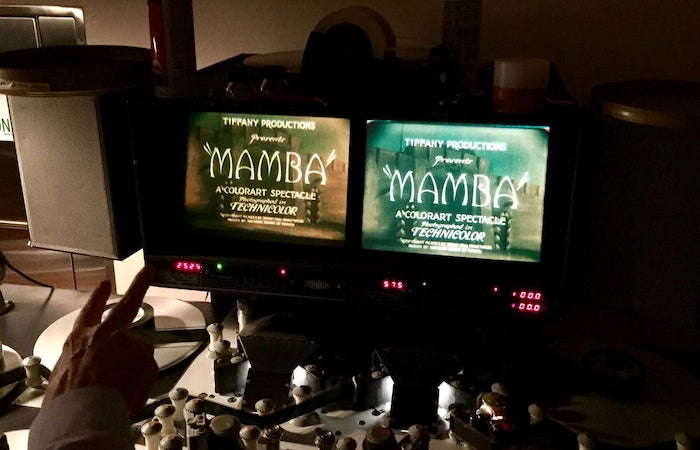

There was a whole section in Hollywood that was jokingly referred to as “Poverty Row,” where all the fly-by-night independent producers rented space to make low-budget films. They could shoot a western in 2 or 3 days for as little as $10,000 dollars; they were really take-the-money-and-run kind of guys. These little producers included Ajax Pictures, Sunset Productions, Chesterfield-Invincible, Majestic and Monogram. Tiffany was one of the major Poverty Row studios that seemed to have a little bit more money and wherewithal to hire better talent. For example, Mamba was a half-million dollar production in two-color Technicolor and sound in 1930. They hired name actors like Jean Hersholt and Eleanor Boardman, who had been a very popular silent actress at MGM. It's “Poverty Row” in that it was shot by an independent studio, but they rented space at Universal and tried to make it as close to an “A” picture as they could. They were trying to elevate themselves.

But most of the Poverty Row films came and went because they were substandard quality; they didn't have big stars so they didn't survive well. They tended to be shot quickly and cheaply, without the time to do lighting setups or retakes. It's much like live television of the 1950s that way, you had one rehearsal and if you flubbed it on the air, that's the way it went out. There's a certain charm to that at times.

Mamba (1930) after color correction (left) and before (right)

Some of the Poverty Row films have withstood the test of time and are now cult classics. For you, what makes Poverty Row productions unique or appealing?

There are gems that surfaced in Poverty Row and the two Edgar G. Ulmer pictures we're showing are good examples of that. With Strange Illusion (1945), they took the broad outlines of Hamlet and slapped them into a 1940s film noir, shot in a week or less. Ulmer tried to bring art with that speed and efficacy, going for the interesting angle and shooting a picture almost in his head, predesigning his shots for maximum effect.

Poverty Row films frequently tackled subjects outside the mainstream, like Ulmer’s Damaged Lives (1933), which addresses venereal disease. They dealt with such subjects because they were exploitable, like forbidden fruit that could attract a desperate audience. Damaged Lives was financed with educational intentions by the Canadian Social Health Council. With these sex or social hygiene pictures, they would "four wall" (or rent) small independent theaters and bring out their expert or pseudo-doctor to sell you pamphlets. For a dime, for a quarter, just to make more money.

The better examples of Poverty Row films, I think they're intriguing because they do things that the major studio films couldn't or wouldn't do. There's something exciting about seeing a filmmaker, given almost no resources, every now and then shoot something notable for a buck and a half. There are also the unintentional joys of humor in the high school pageantry of some of the Poverty Row pictures.

Director Edgar G. Ulmer (left) on the set of Damaged Lives (1933)

Why are they worthy of preservation?

If an archive will not save them, no one will. Many of them are already gone or just hanging by a thread. Nobody wants to put a lot of money into Poverty Row films; they don’t have a commercial return and don't seem to excite a lot of funding agencies the way a Jeanette MacDonald, Garbo, Clark Gable or a Technicolor picture do, which is sad because they are in greater need.

Tell us about a Poverty Row film the preservation team is working on now.

Film Preservationist Miki Shannon is working on Hearts of Humanity (1932), an interesting melting pot saga of Jewish and Irish Americans in the Lower East Side. When an Irish cop is killed, his friend, a Jewish pawnbroker, adopts the cop's son. It's a real old New York story of immigrants and tolerance among disparate groups. For a reason like that alone, it's well worth saving. The initial difficulty was finding a clean, complete copy. The challenge now is to find the funds to complete the restoration.

There's another we'd very much like to preserve called Nation Aflame (1937), which is about the Ku Klux Klan. We were able to obtain a print recently. It doesn't address the Klan's persecution of African Americans, it simply portrays them as a hate group going after the general “other.” It was produced by Edward and Victor Halperin, who also produced White Zombie (1932) and were very busy on Poverty Row. When the print of Nation Aflame came in, much of it had nitrate decomposition. There's a print at the Library of Congress that's in trouble as well.

False Faces (1932)

Among the films we’re showing in this series, is there a title you’re especially fond of?

False Faces (1932) is probably my personal favorite of the batch. It's a deliriously fine Poverty Row film by a major director, Lowell Sherman, who also stars in it as a corrupt plastic surgeon. Sherman died in 1934, a few weeks into shooting Becky Sharp (1935), the first three-color Technicolor film. He was no slouch. We had at the Archive the camera negatives, decomposing and incomplete. The Academy Film Archive owned a nitrate print, also decomposing and incomplete. Our colleague, film historian David Stenn, found a 16mm print that had vinegar syndrome but included the shots, climactic sequence and ending we needed to make False Faces complete. It's as fine as any of the Warner Bros. muckrakers of the period, a really tough, nasty, cynical, well-made film. I'm also fond of The Vampire Bat (1933) in a jokey pleasure kind of way. I was very happy with the restoration because it gave us the opportunity to restore its long-lost hand-colored sequence by Gustav Brock.

The Vampire Bat (1933)

Down and Dirty in Gower Gulch screens Oct. 27 - Dec. 8 at Raleigh Studios, opening with a fundraising gala for film preservation.

Special thanks to The Packard Humanities Institute, The Film Foundation, the George Lucas Family Foundation, the Franco-American Cultural Fund, the AFI/NEA Preservation Grants Program, and the National Archives of Canada for funding these six preservation projects.

As a non-profit organization, the Archive depends entirely on the support of grants, foundations and individual donors to achieve its preservation goals. Learn about how you can make a contribution.

—Jennifer Rhee, Digital Content Manager

< Back to the Archive Blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation

Comments