Even though I have been studying German silent cinema for more than four decades, I had not previously heard of the name Hanns Brodnitz, at least not until my recent trip to Berlin, when my long time colleague at the Deutsche Kinemathek, Gero Gandert, gave me a remarkable book by him [1]. Brodnitz’ Kino intim (unfortunately only in German) was supposed to have been published in April 1933, authored by one of Berlin’s most highly regarded exhibitors, the former Director of the independently operated Mozartsaal am Nollendorfplatz (1923-25, 1930-31), the giant Capitol and Marmorhaus cinemas (1925-28), and finally, the head of all the UFA’s first run cinemas (1928-30), among others. The book never appeared, due to the Jewish boycott by the Nazis, with Brodnitz losing his job the same fateful month; the former boy wonder now unemployable at the age of 32. For the next 11 years, Brodnitz lived more or less underground, but was finally caught and sent to Auschwitz, where he was murdered on October 1, 1944. Amazingly, the page proofs for his book survived and were rediscovered in 1990, leading to their printing 72 years after their original publication date.

Brodnitz presents a n insider’s view like no other of the Berlin film exhibition market in the 1920s, describing both incredible successes that no one wanted to show (People on Sunday, 1930) and total flops (Erich von Stroheim’s The Merry Widow, 1925). Berlin audiences were apparently ready to riot any time a film didn’t meet their expectations. The most famous event of that kind was the opening of All Quiet on the Western Front (1930),which Brodnitz personally organized after no one else in Berlin was willing to take the film. The film received rave reviews from critics and the public at its premiere, but Nazi Storm Troopers put an end to any further screenings, in the process destroying the exhibitor’s career. But it is the tidbits that are most fascinating, e.g. the role of scalpers. Brodnitz notes that he always knew when a film was going to be a hit or a miss, based on the activity of the scalpers, who always had a pulse on the moods of Berlin audiences and would accordingly buy or avoid buying advance tickets for a particular show. Like the beggars in The Threepenny Opera (1931) or the small time criminals in M (1931),the scalpers had their own union, employing women and children as their runners to sell tickets at “sold out” events. Who would have guessed?

n insider’s view like no other of the Berlin film exhibition market in the 1920s, describing both incredible successes that no one wanted to show (People on Sunday, 1930) and total flops (Erich von Stroheim’s The Merry Widow, 1925). Berlin audiences were apparently ready to riot any time a film didn’t meet their expectations. The most famous event of that kind was the opening of All Quiet on the Western Front (1930),which Brodnitz personally organized after no one else in Berlin was willing to take the film. The film received rave reviews from critics and the public at its premiere, but Nazi Storm Troopers put an end to any further screenings, in the process destroying the exhibitor’s career. But it is the tidbits that are most fascinating, e.g. the role of scalpers. Brodnitz notes that he always knew when a film was going to be a hit or a miss, based on the activity of the scalpers, who always had a pulse on the moods of Berlin audiences and would accordingly buy or avoid buying advance tickets for a particular show. Like the beggars in The Threepenny Opera (1931) or the small time criminals in M (1931),the scalpers had their own union, employing women and children as their runners to sell tickets at “sold out” events. Who would have guessed?

Brodnitz also writes about many film personalities in the Berlin cinema world, including Sam Rachmann, who I have personally been trying to track down for at least two decades, having been written about as the “German-American businessman” as a central figure in bringing Madame DuBarry (1919)toAmerica, the founding of the European Film Alliance (EFA), and the Parufamet contract that bailed out the UFA and gave control of its first run cinemas to the Americans. For a few years the Berlin film trades were filled with his excesses, including fancy hotel suites, big cars and oodles of Kurfürstendam prostitutes—a lifestyle as crazy as Berlin’s inflationary period. As far as I could tell, though, Rachmann came out of nowhere and disappeared into nowhere. In point of fact, Rachmann was born in Galicia in 1877 and may have emigrated to the United States, but by World War I was working in Berlin as a manager for acts in vaudeville. Brodnitz writes politely: “His education was more modest than modest, his manner not always urbane, his business practices not necessarily fair. But despite opaque transactions, he developed a form of mediation that lead to reconciliation… The most cold-hearted anti-Semites succumbed to his influence, e.g. Herr von Stauss, Director of the Deutsche Bank, who loved negotiating with him” (Brodnitz, p. 126). Von Stauss was the Chairman of the Board of UFA, and made Rachmann head of all exhibition, but Rachmann died a pauper in 1930, apparently owing more than RM 20,000 to Pola Negri and other film personalities. He would share that fate with many other pioneering German film producers and exhibitors.

At another point, the author writes about Curtis Melnitz, a well-known press agent, the Berlin rep for United Artists, and the father of William Melnitz, of Melnitz Hall (UCLA) fame, former Max Reinhardt associate and Dean of Fine Arts at UCLA. Melnitz’ père organized Charlie Chaplin’s infamous tour to Berlin in 1931 for the premiere of City Lights, another event marred by Nazi-led anti-Semitic riots.

At another point, the author writes about Curtis Melnitz, a well-known press agent, the Berlin rep for United Artists, and the father of William Melnitz, of Melnitz Hall (UCLA) fame, former Max Reinhardt associate and Dean of Fine Arts at UCLA. Melnitz’ père organized Charlie Chaplin’s infamous tour to Berlin in 1931 for the premiere of City Lights, another event marred by Nazi-led anti-Semitic riots.

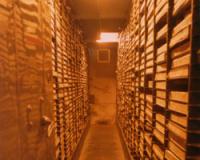

Surprisingly, Brodnitz also calls for the establishment of film archives: “...anyone who has studied film culture for more than a decade must be alarmed by the carelessness with which so much culturally valuable material is treated, given its importance for future generations. It should be a matter of course that a state-owned film archive protect at least one copy of any interesting film. In reality, though, the negatives of successful films are run into the ground, so that it is today no longer possible to produce a decent print. That is especially true for seminal works of film art, whose value is more than just a reflection of history. But the great majority of films from the pre-war period also no longer exist in any form, not even the important newsreels… This is one reason why it is impossible to run a repertory house, which would show those films of importance to film history…”

Both the Reichsfilmarchiv, the Museum of Modern Art Film Library, and the Cinémathèque Française would come into existence in the three years following the suppression of Brodnitz’ book.

[1] Hanns Brodnitz, "Kino intim. Eine vergessene Biographie." Edited by Gero Gandert and Wolfgang Jacobsen. Teetz, Germany: Hentrich & Hentrich, 2005.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation

Comments