Reinhold Schünzel, actor and director

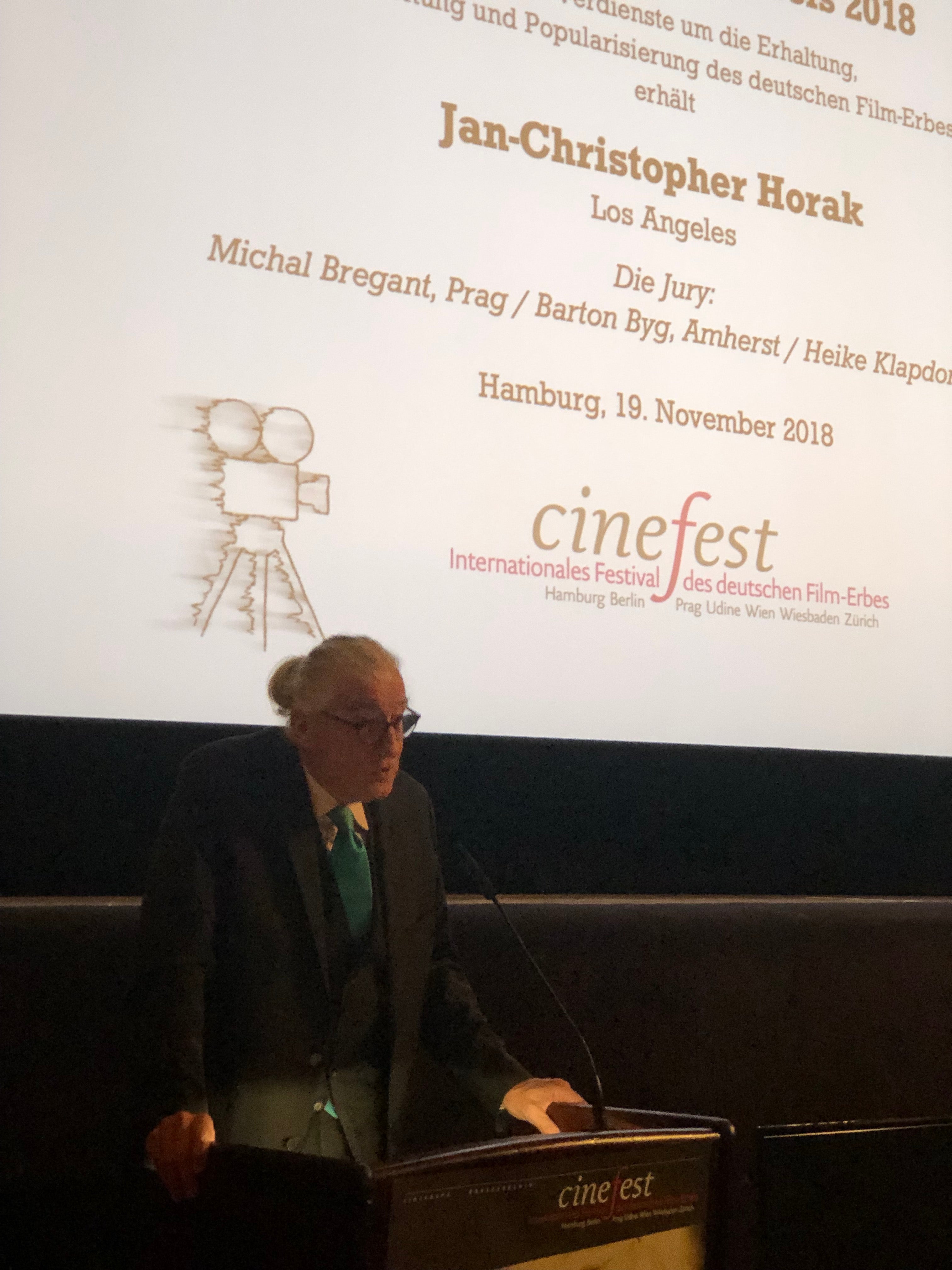

Here is a loose translation of my acceptance speech for the Reinhold Schünzel Award, on November 17, 2018, from Cinefest in Hamburg:

Ladies and gentleman, Hans-Michael Bock, members of the CineGraph team: Thank you, Karl Griep for your words of praise. It is an incredible honor to accept the Reinhold Schünzel Award. I’ve had a long career, and I’m assuming it is my work on German exile cinema that has brought this recognition, but I have to admit, I did not do it alone. Rather, dozens of colleagues have supported my research and publications over the years.

When I first traveled to Los Angeles in the summer of 1975, in order to interview German-speaking film artists who were forced to flee Nazi Germany after 1933, I had no idea that this project would preoccupy me for a lifetime. I had completed research in Germany a year earlier for my master’s thesis on Ernst Lubitsch and thought it would be interesting to see who else had made the journey to Hollywood from Lubitsch’s circle and beyond. Funded by the Louis B. Mayer Foundation Oral History Program, I was able to interview Henry Koster, Hans Brahm, Wihelm Thiele, Walter Reisch, Joe Pasternak, Walter Kohner, Celia Lovsky and John Mylong-Münz, among others. While in L.A., I was offered a post-graduate internship at George Eastman Museum where I spent the year, attempting a first filmography of German-Jewish refugees to Hollywood.

My interest in exile was, of course, also personal. I did not consider myself an émigré, but my family emigrated to the United States as displaced persons. My father was arrested by the Gestapo after the Nazi invasion of Czechoslovakia and sent to KZ Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg; in 1948 he fled the country after the Communist putsch. My mother, a German national born in Cologne, lost her German citizenship and became stateless when she married my father in 1949, because of a Nazi law about keeping German blood pure. At eight months old, my parents, my twin brother and I immigrated to America. I would have grown up an ordinary American, except for the fact that my parents decided to return to Germany when I was 13. For a kid going through the throes of puberty, it was a massive culture shock. As my parents later admitted, in returning, they made us stateless, at least in our heads, if not legally, since we were now American citizens. Since then I have been half American, half German, and also Czech, truly at home everywhere and nowhere.

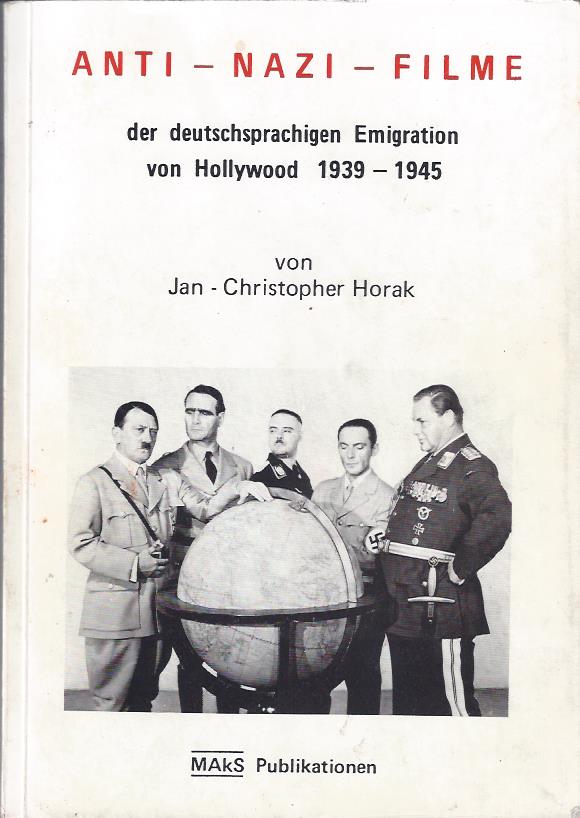

So I began researching German-Jewish exiles in the film industry. In an age before IMDb.com and other lexica, I had to figure out who had left Germany and who ended up in Hollywood, an extremely labor-intensive task, as I soon realized. I searched through older works, like the Italian Filmlexicon degli autori e della opere (1959-1962), as well as Film Daily Yearbook, Alfred Bauer’s Deutscher Spielfilm Almanach and all published autobiographies, using note cards; we were still analog back then. Only when I got to Münster to start a Ph.D. under Prof. Winifried B. Lerg did I realize that there was an academic field in formation, called German exile studies, as well as another filmographic project by Günther-Peter Straschek, heavily funded by the German Science Foundation. A few excerpts of his work were published in the Handbuch des deutschen Exils and I also eagerly viewed his TV documentary, Filmemigration from Nazi-Germany. When I wanted to publish my filmography of over 500 émigrés as a part of my dissertation on anti-Nazi films made by German émigrés, I hesitated because I knew Straschek’s work would supercede ny own, but it remains unpublished to this day. One can only hope that a project headed by Dr. Imme Klages at the University of Mainz will make this important material available in the future.

There was a focus on exile research at the Communications Institute in Münster, which gave me a theoretical and ideological framework that I was previously lacking in my American education. Martia Hilfenbach had published her dissertation under my thesis advisor shortly before my arrival: Emigration of German Film Artists. My colleagues working in the field included Elke Hielscher und Sigrid Schneider, who had published her dissertation on German exile literature and would become my most trusted critic in the coming years. Through her, I learned not only of important exile publications, like Freies Deutschland Mexiko und Der Aufbau, but also of colleagues in the field, like Thomas Koebner, Wulf Köpke , Ernst Loewy, Wolfgang Gersch, Joachim Radkau, Hans-Bernd Moeller and later John Spalek, whose Deutsche Exil-Literatur seit 1933. Kalifornien included important research on exiled scriptwriters.

I also became a member of the Münsteraner Arbeitkreis für Semiotik, a cooperative headed by students Charlie Möller Naß, Hans-Jürgen Wulf und Prof. Joachim Paech. Together we founded a journal, film theory,and a press, which would later publish my dissertation. But it was the intense discussions about the nature of film language that gave me the academic instruments to write a dissertation. During my years as a grad student, I also met American Germanists Eric Rentschler und Tony Kaes, who both had a huge influence on my work. I also established contact with the Stiftung Deutsche Kinemathek, which invited me to work on several retrospectives at the Berlinale film festival, and allowed me to attend their program, Exile: Six Actors from Germany in 1982, and further retros in later years on Otto Preminger, Billy Wilder and the Siodmak brothers. Meeting Hans-Helmut Prinzler, Wolfgang Jacobsen, Werner Suddendorff, later Rainer Rother, further expanded my horizons. I should also mention the important but short-lived publication, Film Exil, edited by Heike Klapdor, among others. Other colleagues who I have benefited from knowing include Helmut Asper, Michael Omasta, Thomas Tode, Geoff Brown, Klaus Kreimeier, Michael Töteberg, Hans-Christoph Blumenberg, Thomas Brandlmeier, Joseph Garncarz and Karsten Witte.

Quite surprisingly, my dissertation, Anti-Nazifilme der deutschsprachigen Emigraion, 1933-1950,became a bestseller at the press, possibly because it was the first serious analysis of the work of German émigrés in Hollywood. When I took a position as curator at George Eastman Museum I thought I had put the topic of exiles behind me, but it has grabbed me repeatedly over the years, especially through my cooperation with CineGraph, which has become a center for exile research since the 1990s. As this year’s retrospective on Joe May demonstrates, the topic has hardly been exhausted. There are always new discoveries, so I’m excited about my own future projects in the field and the new work of my colleagues. Research is always a community activity and it has been my great privilege to belong to that community. Thank you.

< Back to the Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation