Two-color Kodachrome

For the last eight years, Barbara Flueckiger has been on a mission to create digital research tools for the study of color film technology and aesthetics. A professor in Film Studies at the University of Zurich, Flueckiger has been presenting papers on her ongoing research and website development at conferences hosted by the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF), the Association of Moving Image Archivists (AMIA), and other archive organizations. In July 2017, Flueckiger spent a couple of weeks at UCLA Film & Television Archive making frame enlargements from the Archive’s nitrate film collections, which are now online with similar images from the Library of Congress, the National Science and Media Museum in Bradford, England, and other institutions.

The project is impressive and ambitious. Flueckiger began her career as a film critic, before switching to the technical side of film production, becoming a sound designer who worked with internationally respected directors like Claude Goretta. Only after that phase did she embark on an academic career, but she has never given up a practical bent to her research. After publishing her dissertation, Sound Design – The Virtual Sound World of Film (2001), she completed her habilitation (post-doctoral qualification), Visual Effects. Digital-Analog Forms of Representation in Films (2007), a comparison of digital and analog film materials. So, Flueckiger was well-prepared to take on her current massive project, which questions how the reproduction of film color in the digital realm is different from the analog originals.

She began her quest in 2011, when she received a grant to conduct research on historical color processes at the Harvard University Department of Visual and Environmental Studies. The results of that effort were first published in 2012 on her “Timeline of Historical Film Colors,” and then expanded to a “Database of Historical Colors,” funded by a crowdsourcing campaign, the University of Zurich, and the Swiss National Fund. In 2015, Flueckiger received an Advanced Grant of 2.9 million euros from the European Research Council for her project, “Film Colors. Bridging the Gap Between Technology and Aesthetics.” This prestigious grant is “awarded to leading European researchers who have shown outstanding achievement in their field over the last ten years and who should be afforded the freedom they need to pursue their research through attractive new projects.”

“Timeline of Historical Film Colors” website

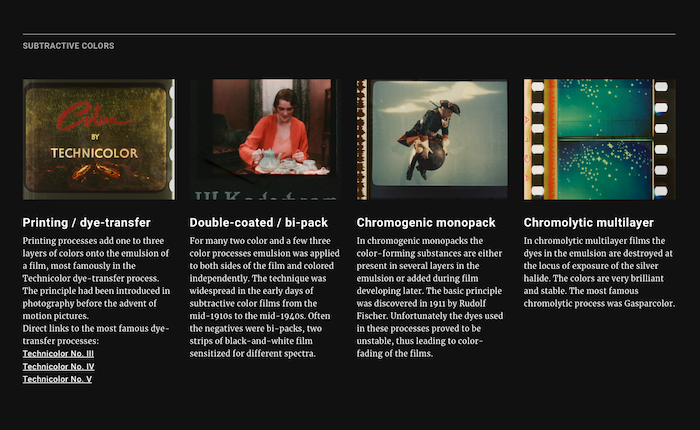

The “Timeline of Historical Film Colors” is organized chronologically by the first appearance of the technology. The first pages introduce 19th century color theory, beginning with scientists Thomas Young (1802) and James Clerk Maxwell (1861), before discussing numerous color processes, including the Ernest Edwards dye imbibition process (1875), tinting (1896), Autochrome (1907), etc. There are more than 400 entries and thousands of images, although many of the newer Kodak film stocks have not yet been populated with data or images. Each entry includes the name of the process, date of invention and inventor, followed by a brief description of the process and a gallery of images. Thus, for Two-Color Kodachrome (1915), later known as Fox Nature Color (1930), the gallery includes more than more than 128 frame enlargements from four sources: Hat Fashions (n.d.), Kaleidoscope (n.d.), The Flute of Krishna (1926), Kodachrome Two-Color Samples (n.d.). All of the digital photos were made from original nitrate prints by Flueckiger herself. In many cases she reproduces not only the film prints, but the black-and-white negatives and other technical drawings to help visualize the process. Flueckiger emphasizes that the workflow for reproducing images (equipment, light sources, etc.) remains rigorously the same for each scan, thereby guaranteeing that there will be a basis for comparison. The database is a truly excellent resource for anyone studying color film processes.

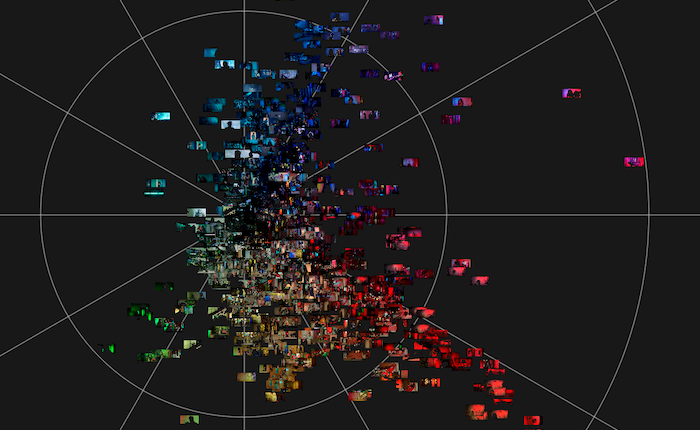

Mapping the colors of Suspiria (1977)

The present ERC Film Colors project goes much further, however, slicing and dicing the collected information in all kinds of ways. According to the website: “Beyond the analysis of hues and color contrasts of figures and backgrounds, the protocol required the analysis of locations and periods, narrative and semantic concepts, characters’ affective and emotional states, image composition, lighting, patterns and textures, and surfaces and properties of characters, objects and environment.”

Obviously, technical specifications of different scanners also play a role in the reproduction process, so Flueckiger has also conducted a study under the aegis of DIASTOR, which investigates seven different high-end scanners with eight different film stocks, focusing on scanner-material interaction, rather than primarily on technical quality.

This research will be invaluable, especially as film preservationists continue to restore more and more legacy material in digital form.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation