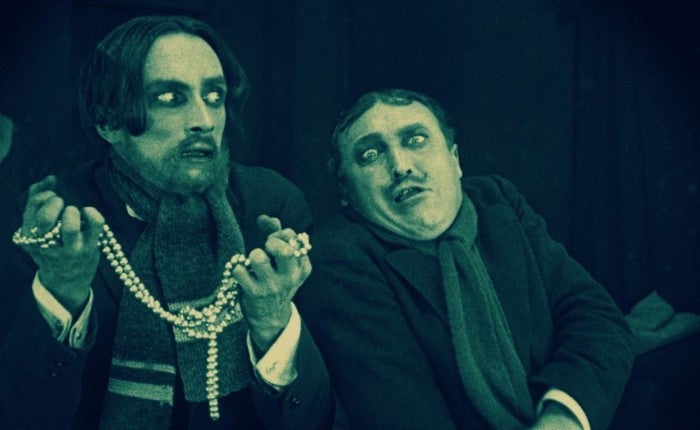

Abwege (1928)

At this year’s Berlinale, the Deutsche Kinemathek organized Weimar Cinema Revisited, a retrospective that eschewed the German Expressionist classics of the 1920s and focused on Weimar’s many genres and “middle” films, rather than art cinema. The Weimar program included avant-garde films (Hans Richter’s Inflation, 1928), travel documentaries (People in the Bush, 1930), melodramas (Out of Wedlock, 1926), historical films (Ludwig II, 1929), comedies (Heaven on Earth, 1927), and musicals (Her Majesty, Love, 1932), both silent and sound. I would have liked to see all 26 features and the handful of shorts, but managed to catch a significant number of discoveries. I did miss the big event, the digital restoration of Das alte Gesetz [The Ancient Law] (E.A. Dupont, 1923), a rare Jewish-themed film.

First, there was Christian Wahnschaffe (Urban Gad, 1920), starring Conrad Veidt as a wealthy son of a factory owner who gets caught up in the 1905 Russian revolution. Directed by Asta Nielsen’s ex-husband, and based on a novel by Jakob Wassermann, the film’s two feature-length parts were written and shot by two different teams, which shows in both the editing and narrative construction, the latter already weakened by missing and decomposed footage. In Part 1: World Afire, the hero falls prey to a Parisian dancer, who betrays the revolution, á la Madame Dubarry. Part 2: The Escape from the Golden Prison finds the hero renouncing his wealth after protecting and then trying to save a prostitute from her pimp. These are metaphors for the German experience of war and postwar, respectively. My attention was held by Fritz Feld in a rare surviving performance in German cinema. Feld became a fixture as a character actor in American film comedy; he had moved to Hollywood after completing Max Reinhardt’s “The Miracle” tour in 1923. I had the pleasure of interviewing him in the 1970s for my German exiles oral history project.

Christian Wahnschaffe (1920)

Visual history was also very much in evidence in Gerhard Lamprecht’s drama of the Napoleonic Wars in Germany, Der Katzensteg [The Sins of the Father] (1927). Based on a Hermann Sudermann novel, the film presents an extremely ambiguous view of patriotism, when a small town ostracizes a local nobleman, whose father had betrayed the Prussians to the French. Given that virtually every German film about Prussia vs. France goes hard right for nationalistic ideology, Katzensteg privileges Lissy Arna’s maid who fights her way from servitude to independence, as an object of identification for young German women. Unfortunately, the 16mm print that was screened (a dupe from Lamprecht’s own print) was totally out of focus and practically unwatchable. I first saw the film at Eastman Museum many years ago, and heard that there is 35mm material in eastern Europe, so one can hope a future digital restoration is in the works.

Focusing on an impoverished petit bourgeois woman who comes into class-consciousness, Das Lied vom Leben [The Song of Life] (1931) was likewise in relatively poor condition, suffering from censorship cuts and the degraded state of the only surviving material. A Cesarean birth scene was heavily censored. It is unclear whether the film’s elliptical narrative was intentional or the result of lost footage. The opening scene was staged as a Dadaist film happening: the “heroine” must marry an old count for his money. After the wedding, she flees into the arms of a working class hero. Directed by the Russian-Jewish exile Alexis Granowsky, and written by leftist sympathizers Walter Mehring and Victor Trivas, the film is a tour de force of Soviet-style editing. Through all the damage, one can see an energetic film musical, accompanied by Brechtian songs, composed by Hanns Eisler and Friedrich Hollaender, and sung by Brecht favorite, Ernst Busch.

Der Katzensteg (1927)

Brecht’s “Pirate Jenny” turns up in Die Carmen von St. Pauli (Erich Waschneck, 1928), where Jenny Jugo plays a petty thief and nightclub performer in Hamburg’s infamous red light district. Like Carmen, she seduces a sailor who then neglects his duties and then seemingly abandons him for a rich suitor. The location scenes in St. Pauli and around the harbor are documentary-like in their realism, but true to the UFA style, the film ends happily, not like Carmen’s operatic tragedy, because Jenny reveals herself to be an independent woman.

Another comedy that could have turned into a tragedy also centers on “the new woman.” Das Abenteuer einer schönen Frau [The Adventure of Thea Roland, 1932] stars Lil Dagover as Thea Roland, an upper-class artist who decides to have a child out of wedlock after a night of romance with a boxer. Like her ultra modern art deco apartment, Thea embodies the sexually and socially liberated woman. Henry Koster’s directorial debut is a comedy of manners and class prejudice. The heroine’s upper-class friends abandon her because of the scandal, while the boxer just wants to get married when he realizes he is a dad. Within months of the premiere, Koster would flee Berlin as a Jew, while the new woman would disappear, supplanted by Nazi Germany’s ideology of the pliant Hausfrau.

Die Carmen von St. Pauli (1928)

However, the most modern film in the retrospective was G.W. Pabst’s Abwege [The Devious Path, 1928], presented in a new digital restoration. Starring Brigitte Helm as the bored wife of a wealthy lawyer, the film subtly displays the breakdown of a marriage, as both partners are seemingly unable to communicate their feelings to each other, their displeasure coded through minute movements of lips and eyebrows. Meanwhile, the search for excitement is embodied in a continuously moving camera that glides through the luxurious world of nightclubs, drugs and kept women of 1920s Berlin. It is the economy of its means, embodied in Pabst’s precision editing—the film was produced as a quota quickie—that makes Abwege an unqualified masterpiece of Weimar modernity.

Accompanying the retrospective is a book publication, Weimarer Kino neu gesehen, edited by Karin-Herbst-Meßlinger, Rainer Rother and Annika Schaefer.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation