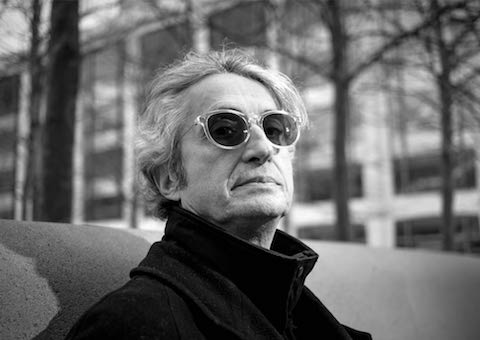

Luis Ospina

Filmmaker Luis Ospina was in town a couple of weeks ago when Los Angeles Filmforum presented a program of experimental films from Latin America called Ism, Ism, Ism at the Billy Wilder Theater. I initially heard about Ospina in 2016 from L.A. Rebellion filmmaker Billy Woodberry and we had an initial email exchange, since Ospina was not only a student at UCLA Film School (1969-1972), but also one of a number of foreign students in the department at the time, including Dominican filmmaker Jean-Louis Jorge (who was tragically murdered in 2000) and French filmmaker Jean-Marie Bénard. Like the Chicano and Asian-American students in the film school, they all felt closer to the spirit of the yet unnamed “L.A. Rebellion” than to their Caucasian cohorts. Over lunch we discussed the need to recuperate the history of these other students, as Ospina remembered Charles Burnett, Larry Clark and Billy Woodberry.

At UCLA, Ospina made three films: Acto de fe (Act of Faith, 1972), an adaptation of “Erostratus” by Jean-Paul Sartre, which was his Project One student film; Oiga vea (1972), a political documentary (and thesis film) about the 6th Pan-American Games in Cali, Colombia; and the experimental Autoretrato (Dormido) (1971). He then returned to his native Colombia, where he has had a long and successful career as a filmmaker, curator and essayist. He has in fact made more than 30 films, including two fiction features, seven feature-length documentaries and more than 20 experimental and documentary shorts. Ospina’s most recent film, Todo comenzó por el fin (It All Started at the End) premiered at the 2015 Toronto International Film Festival. It is a highly autobiographical documentary about the Cali Group or “Caliwood,” a group of Colombian filmmakers active from 1971 to 1991, which included Ospina.

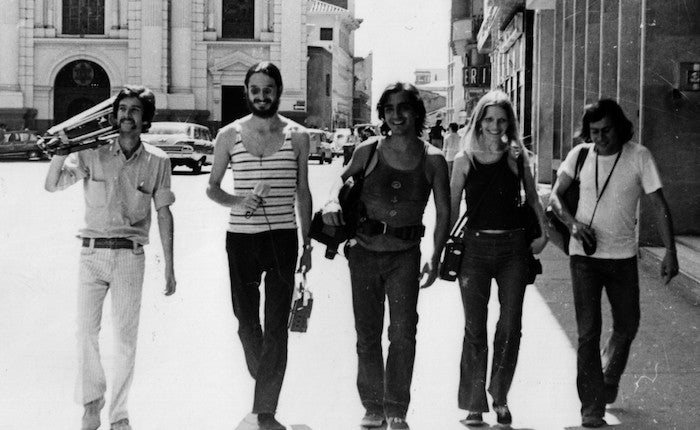

The Cali Group in Todo comenzó por el fin (It All Started at the End, 2015)

For the Ism, Ism, Ism program, Ospina presented one of his most well-known works, Agarrando pueblo (The Vampires of Poverty, 1977), which he made with Carlos Mayolo. This black and white “mockumentary” follows a film crew around the slums of Bogotá, which is attempting to produce a documentary for West German television. The director and his cameraman shove the camera into the faces of any beggars they can find, wishing to capture only the most squalid images possible, then hightail back to the safety of their car when they encounter the slightest resistance. In a subsequent scene, the crew directs a group of street urchins to jump into a public fountain for the pennies they throw, leading the crowd of locals to question openly the motive of the filmmakers, accusing them of exploiting the children. Finally, the team breaks into a shack that is inhabited but empty, interviewing several actors as if they were the inhabitants. However, as they complete their shoot, they are confronted by the shack’s owner, who screams at them for invading his privacy. The filmmakers then interview the aggrieved tenant.

Agarrando pueblo (The Vampires of Poverty, 1977)

According to Luis Opsina during a post-screening discussion, the film was a critique of two phenomena. First, a new film law in Colombia at that time required the projection of a Colombian short film with any foreign features, leading to an incredible over-production of films by novice filmmakers only interested in producing something for sale. Secondly, the film was also a critique of the so-called post-liberation Latin American cinema, which insisted that only left-wing documentaries on the exploitation of Third World peoples by American and native capital were a legitimate form of expression, while all Hollywood-style narratives were to be condemned. The “vampires of poverty,” then, are filmmakers who unwittingly exploit the very people they are attempting to liberate from poverty; they remain tourists of squalor, because they are not really interested in hearing the stories of their subjects.

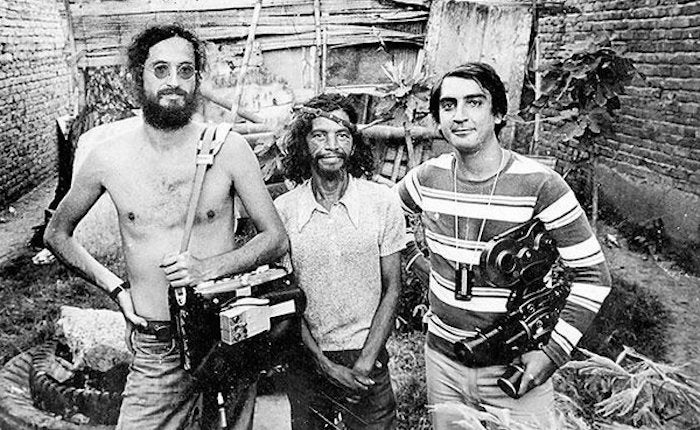

Un tigre de papel (A Paper Tiger, 2007)

Luis Ospina’s healthy skepticism of revolutionary dogma is also reflected in a feature-length film essay, Un tigre de papel (A Paper Tiger, 2007), about the Columbian collage artist, poet and sometime revolutionary, Pedro Manrique Figueroa. PMF, as he is sometimes referred to in the film, disappeared without a trace in 1981, but is also an enigma because virtually no images of the artist or many of his collages survive. Two of his found footage films do exist and are included in the essay, along with footage from various Communist propaganda films, newsreels and interviews with contemporaries. Born in 1934, and strongly influenced by the murder of leftist politician Jorge Eliécer Gaitán in 1948, when he was a ticket collector on a tram, we learn that Figueroa was trained as a professional revolutionary in East Germany in the 1960s. He travelled to Eastern Europe and China, but also spent a good portion of his life homeless, an intellectual who floated in and out of Bogotá’s coffee house scene, distributing homemade pamphlets, leaflets and collages, which reflected his own strange mixture of Communist, Socialist and Maoist ideologies with a healthy dose of sexuality. Ospina’s portrait of an artist who never quite fit in is also, then, a social and political history of Colombia’s turbulent past.

Watch a conversation with filmmakers Luis Ospina and Jesse Lerner at the Billy Wilder Theater:

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation