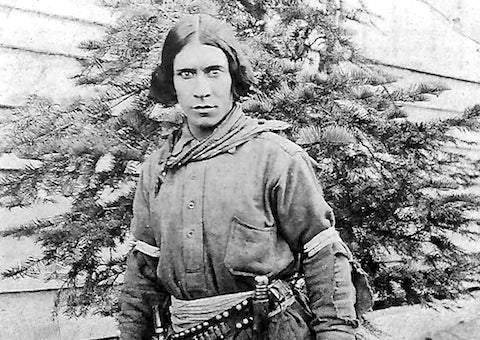

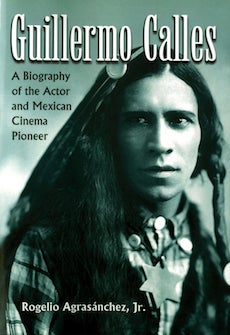

During the recent symposium, “Hollywood Goes Latin: Spanish-Language Cinema in Los Angeles,” which we hosted with the Academy Film Archive, my ears perked up during a presentation by Rogelio Agrasánchez, Jr. on the Mexican filmmaker Guillermo Calles, who was from the indigenous Tarahumara tribe of Chihuahua, and had been very active in American silent films. I had not been aware of Calles when we did Through Indian Eyes: Native American Cinema in 2014 — the series was focused on aboriginal people north of the Rio Grande —, so I turned to Agrasánchez’s book, Guillermo Calles: A Biography of the Actor and Mexican Cinema Pioneer (2010) to read up on this fascinating personality.

Born in Chihuahua City in 1891, Calles grew up dirt poor in Arizona mining towns, moved to Los Angeles in 1912, and started getting roles in films by Siegmund Lubin and Cecil B. DeMille. However, Calles’ acting career really took off in 1918 when he received major supporting roles in a series of Vitagraph serials, starring William Duncan and Edith Johnson, including A Fight for Millions (1918), Smashing Barriers (1919) and The Silent Avenger (1920). “Willie Calles,” as he became known in Hollywood, would become a reliable character actor in American and Mexican cinema over the next 40 years, appearing in at least 90 films, including María Elena (1936), Enamorada (1946), The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948), The Torch (1949), and El bruto (1953).

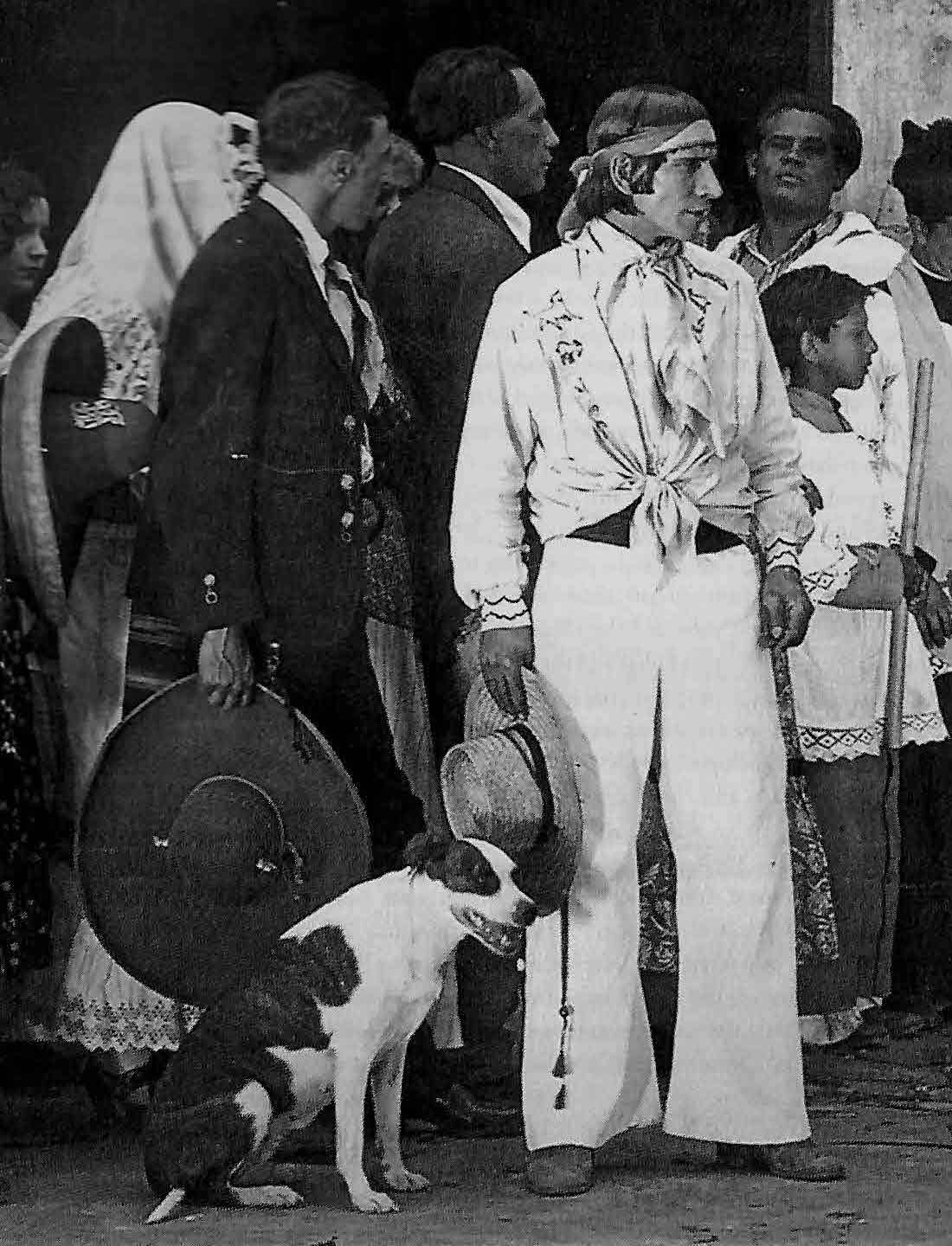

But as Agrasánchez makes clear, Calles was also a Mexican nationalist who decried the stereotypical and racist images of Mexicans and Native Americans circulated by Hollywood cinema. He wanted to direct his own films, so in 1921 Calles joined forces with then film novice Miguel Contreras Torres to produce and direct De raza azteca, in which Calles plays a noble survivor of the Aztecs. Although the film suffered from a lack of budget, some critics praised the positive portrayal of Mexicans and Native Americans. Five years later, Calles used $1,500 of his own money, as well as funds from his actor friends, Neal Hart, Betty Brown and Roy Stewart (who appeared in the film) to produce and direct El indio yaqui at Universal Studios and locations in Sonora, Mexico. The story involving an implied miscegenation finds Calles playing a Yaqui Indian who heroically sacrifices himself, a trope that would reappear in his other independently produced films. The film found grateful audiences in America and Mexico and Calles became so identified with the role that many in later years assumed he was a Yaqui. As one critic noted, the film “reveals to the American people an unknown trait of a race that has been ignored; a race that is idealistic and devoted to beauty….” (p. 54). Unfortunately, none of the films Calles directed in the silent era survive, including Raza de bronce (1927), Sol de Gloria (1928) and Dios y ley (1930), the latter a part-talkie. All of Calles’ films proved to be extremely popular, especially with Main Street Mexican audiences in Los Angeles, where his films were repeatedly reprised.

But as Agrasánchez makes clear, Calles was also a Mexican nationalist who decried the stereotypical and racist images of Mexicans and Native Americans circulated by Hollywood cinema. He wanted to direct his own films, so in 1921 Calles joined forces with then film novice Miguel Contreras Torres to produce and direct De raza azteca, in which Calles plays a noble survivor of the Aztecs. Although the film suffered from a lack of budget, some critics praised the positive portrayal of Mexicans and Native Americans. Five years later, Calles used $1,500 of his own money, as well as funds from his actor friends, Neal Hart, Betty Brown and Roy Stewart (who appeared in the film) to produce and direct El indio yaqui at Universal Studios and locations in Sonora, Mexico. The story involving an implied miscegenation finds Calles playing a Yaqui Indian who heroically sacrifices himself, a trope that would reappear in his other independently produced films. The film found grateful audiences in America and Mexico and Calles became so identified with the role that many in later years assumed he was a Yaqui. As one critic noted, the film “reveals to the American people an unknown trait of a race that has been ignored; a race that is idealistic and devoted to beauty….” (p. 54). Unfortunately, none of the films Calles directed in the silent era survive, including Raza de bronce (1927), Sol de Gloria (1928) and Dios y ley (1930), the latter a part-talkie. All of Calles’ films proved to be extremely popular, especially with Main Street Mexican audiences in Los Angeles, where his films were repeatedly reprised.

In 1930, Calles was able to direct his first Spanish-language sound film, Regeneración, which was shot in Los Angeles and financed by the Areu Brothers acting troupe. Unlike Calles’ western films, this was an urban melodrama with songs. The Great Depression, which sent tens of thousands of Mexican immigrants back to Mexico, and the costly licenses for sound technology initially hindered the production of further independent films, because Calles’ films had mostly been financed by local cinema exhibitors who were now in dire straits. Unable to find work, Calles took a road trip from Los Angeles to Mexico City and shot a nationalist documentary, Pro Patria (1932), which highlighted the beauty of Mexico. Ironically, Calles had trouble booking the film in Mexico City, because exhibitors there were under contract to the American majors and refused to show locally produced Mexican films.

In 1930, Calles was able to direct his first Spanish-language sound film, Regeneración, which was shot in Los Angeles and financed by the Areu Brothers acting troupe. Unlike Calles’ western films, this was an urban melodrama with songs. The Great Depression, which sent tens of thousands of Mexican immigrants back to Mexico, and the costly licenses for sound technology initially hindered the production of further independent films, because Calles’ films had mostly been financed by local cinema exhibitors who were now in dire straits. Unable to find work, Calles took a road trip from Los Angeles to Mexico City and shot a nationalist documentary, Pro Patria (1932), which highlighted the beauty of Mexico. Ironically, Calles had trouble booking the film in Mexico City, because exhibitors there were under contract to the American majors and refused to show locally produced Mexican films.

However, an upswing in the production of Mexican films in 1933 brought a host of Mexicans working in Hollywood back to the capital, including Calles, René Cardona, Emilio Fernández and Ramón Peón. Calles was hired to direct El héroe de Nacozari (1933), which related the true story of a railroad engineer who saves a whole town by driving his train full of explosives to the outskirts before exploding. He followed up that film with El pulpo humano (1933), an apparently forgettable melodrama, and Ramón Pereda’s El vuelo de la muerte (1933), a melodrama about a Mexican pilot who joins the rescue mission to find two lost Spanish fliers.

Unfortunately, it would be another five years before Calles directed again. In 1938, the Calderon Brothers offered to remake his successful silent Sol de Gloria as Pescadores de perlas (1938), whose hero is an unjustly accused Mestizo, a role played by Calles in the original. Within the same year, Calles also directed the rural melodrama, La virgen de la Sierra (1939) and La justicia de Pancho Villa (1939), a film about the Mexican revolution, which he co-directed with the author Guz Águila.

It would be more than 30 years before another Native filmmaker would direct in North America as an independent. Guillermo Calles' incredible achievement as an independent indigenous filmmaker needs to be communicated to a wider public, especially in the Native American community. Thanks to Agrasánchez, we now have his story.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation