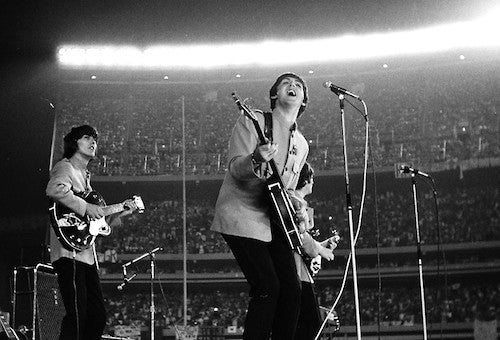

The Beatles at Shea Stadium, 1965

[Continued from my Oct. 14 blog on The Beatles]

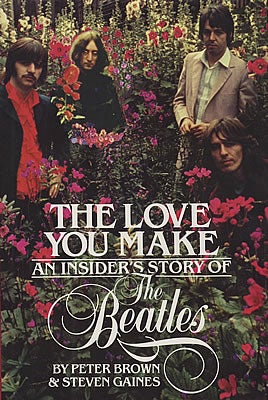

Before my wife and I went to see Ron Howard’s documentary, The Beatles: Eight Days a Week – The Touring Years (2016), I had just finished reading Peter Brown and Steven Gaines’ biography of The Beatles, The Love You Make: An Insider’s Story of The Beatles (1983), which I had picked up in a bargain bin for $2.99. As the title notes, The Love You Make is also an eyewitness account of those same touring years, Peter Brown having been there almost from the beginning as Brian Epstein’s assistant, becoming a member of the innermost circle until the breakup in 1970, while Howard focuses on the Beatles tours from 1962-1966. That gave me a lot of background information, which helped me understand what I was seeing in the film. Eight Days a Week presents footage of The Beatles playing live, hanging backstage, and recording in-studio, as well as archival images of The Beatles being mobbed by fans. The Beatles material is interlaced with footage of Vietnam and the Civil Rights movement, contemporary interviews with the surviving two Beatles, Paul and Ringo, as well as archival interviews with John and George, and interviews with famous fans like Whoopi Goldberg, Elvis Costello and Sigourney Weaver. Amazingly, the filmmakers found a frame of the teenage Weaver in the Hollywood Bowl audience. But as the film’s title suggests, it is the concert footage that really matters.

Interestingly, while almost all of the reviews of Howard’s film either assume the extensive archive footage magically appeared, or quote company press releases that a worldwide hunt for original footage had ensued, I knew where much of the concert footage had originated, having read the book. Brown and Gaines write that Neil Aspinall, another member of the innermost circle (the film is dedicated to Aspinall’s memory among others), tried in 1970 to edit “together thousands of feet of documentary footage on the Beatles that he had gathered over the years, most of it never seen by the public” (p. 379). The resulting film took years to complete and had not been released at the time of the book’s publication, remaining apparently in the vaults of Apple Corp. I also learned that an archive colleague, Matthew White, spent years researching Beatles footage. However, Ron Howard was hired to take the footage and give it narrative shape by focusing almost exclusively on presenting the songs, making it a concert film more than anything else.

Interestingly, while almost all of the reviews of Howard’s film either assume the extensive archive footage magically appeared, or quote company press releases that a worldwide hunt for original footage had ensued, I knew where much of the concert footage had originated, having read the book. Brown and Gaines write that Neil Aspinall, another member of the innermost circle (the film is dedicated to Aspinall’s memory among others), tried in 1970 to edit “together thousands of feet of documentary footage on the Beatles that he had gathered over the years, most of it never seen by the public” (p. 379). The resulting film took years to complete and had not been released at the time of the book’s publication, remaining apparently in the vaults of Apple Corp. I also learned that an archive colleague, Matthew White, spent years researching Beatles footage. However, Ron Howard was hired to take the footage and give it narrative shape by focusing almost exclusively on presenting the songs, making it a concert film more than anything else.

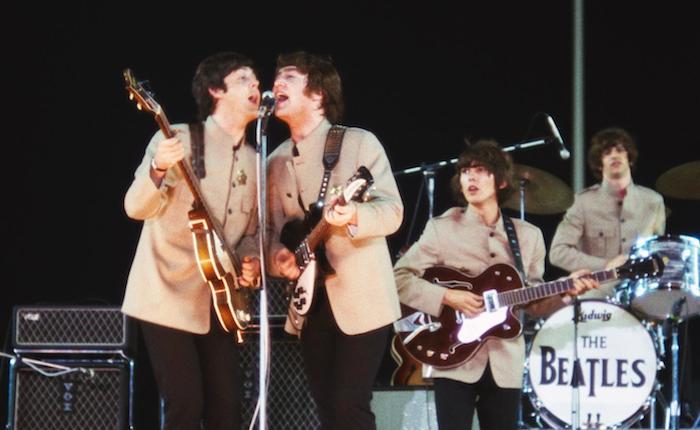

And understood as such, it succeeds magnificently in reconstructing concert footage covering almost all of The Beatles’ early hits, in mostly never-before-seen color footage. For example, the film begins with The Beatles belting out “She Loves You” in Manchester, England, in March 1963, followed later by “Twist and Shout” from the same concert. Over the next two-plus hours, we see The Beatles play in Liverpool (Cavern Club), Hamburg, London, New York, Tokyo, Paris, Los Angeles, Sydney, Stockholm, and finally on a rooftop in London in 1969 for “Let it Be,” years after their last live concert at Candlestick Park in San Francisco on August 29, 1966. As an added bonus, the film tacks on a 30-minute clip of The Beatles at Shea Stadium in 1965.

But the real marvel of the film, however, is the sound production. Virtually all previous Beatles concert footage (including the Shea Stadium concert) suffered from live audio tracks that captured screaming fans, drowning out all the actual music. I suspect no live Beatles LP was ever officially released previously, because of such sound issues. With the help of new digital sound logarithms, created by Giles Martin, son of legendary Beatles producer George Martin, the audience now hears the songs well enough to sing along in their heads. Shockingly, The Beatles sang in tune, even though they could not hear themselves. Actually seeing The Beatles sing allowed me also to understand who sang lead on some cuts, and marvel again at their continual stylistic evolution.

And as one song after another unfolded, tracks I had completely internalized decades ago, I felt an extremely intense mixture of euphoria, nostalgia, and a bit of sadness.

Eight Days a Week has no sins, except those of omission, for example by barely mentioning the continual drug use of The Beatles, beginning with their addiction to speed and downers in the early years to marijuana use with the production of Help! I knew about John’s addiction to heroin from Albert Goldman’s biography, but only learned from the Brown and Gaines book that it had started in London with the arrival of Yoko Ono. Played down completely, too, the continual consumption of groupies, whether married or not. And, finally, the film suppresses any information on the long and bloody breakup with its lawsuits, personal slights and unadulterated cruelty. But do we really need that in this film?

For me, I’ll take the two hours of song and good feeling, happy sharing memories with my compatriots in the dark.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation