She-Devil Island (1936)

A couple of weeks ago we looked at the second answer print of She-Devil Island (1936), the U.S. release version of a Mexican musical melodrama, which IMDb had incorrectly identified as Irma la mala (1936), but is in fact titled María Elena (1936), something I learned from Colin Gunckel, co-curator of our Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA project, Recuerdos de un cine en español: Latin American Cinema in Los Angeles, 1930-1960. She-Devil Island presents an interesting case of how Mexican films were circulated in the United States, since as its English-language version it was distributed as an exploitation picture, although the actual film – unlike the advertising – has little real salacious content. In fact, the film is as much about a tragic unrequited love affair, as it is about the scantily-clad Amazonian women sensationalized in the U.S. release title.

And just as María Elena, a film with art house pretensions, morphs into the exploitation house hit She-Devil Island, the film engages in a transnational exchange of genres, including musicals, rancheros, adventure films, exotic travelogues and melodramas. María Elena (Carmen Guerrero) makes a “bad” choice, allowing sexual desire to trump sensible marriage, thus sending her faithful fisherman suitor across the sea. There, Rogelio (Juan José Martínez Casado) learns of a mysterious island inhabited only by women, and the rich pearl beds on its shores. An adventure film ensues, in which silent “native women” are exchanged by competing groups of males in a jungle locale. Once that gets sorted out, Rogelio learns that María Elena is mortally ill, and returns home, thus returning us to melodrama.

The film’s artistic pretentions are evident in several scenes of Mexican folk music and dance, which were commonplace in the 1930s, when the still-budding film industry was highlighting authentic national culture or Mexicanidad. The opening scene in a fishing village presents men and women in traditional white cotton pants, shirts and embroidered dresses dancing, while a guitar orchestra plays. A later scene has fishermen hanging their nets while singing a folk song, a scene that could have come from Paul Strand’s Redes (1936). Finally, an extended dance scene in a portside tavern features the music “La Bamba,” based on a folk song from Veracruz. The integration of music and dance in other generic film narratives would of course culminate only months later in the production of Allá en el Rancho Grande (1936), the film that inaugurated the ranchero genre and so-called golden age of Mexican cinema.

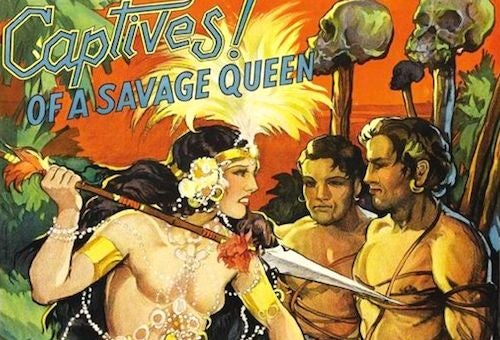

Advertising for María Elena (from Cine-Mundial magazine) and She-Devil Island.

There are several connections between the two films. The original financier of María Elena was Antonio Díaz Lombardo, who had founded Aeroméxico in 1934, but was also involved in the inception of Rancho Grande. Raphael J. Sevilla, the director of María Elena and co-director of La mujer del porto (1934), was also slated to direct Allá en el Rancho Grande, but was then replaced by Fernando de Fuentes. Finally, the composer of the song “María Elena” and the music for “La Bamba” was Lorenzo Barcelata, a native of Veracruz who was also the musical director for Rancho Grande. “María Elena” had originally been composed in 1932 in honor of the wife of Mexican President Emilio Portes Gil. Interestingly, shortly before She-Devil Island’s U.S. release on July 25, 1936, “La Bamba” was performed at the National Dance Teacher's Association convention at the Park Central hotel in Manhattan to create heat for the film.

So, how did this become an exploitation film? Copyrighted as early as November 1935, María Elena was released by Columbia, as posters indicate, and opened at the Teatro Campoamor in Harlem on February 17, 1936. However, the film went nowhere, until Al Friedlander created a lot of ballyhoo with the racy posters for its new title, She-Devil Island. By that time, the film had been purchased by First Division, a Poverty Row producer-distributor that had been taken over by Grand National. When the film opened again on July 25 at the Terminal Theater in Newark, NJ, it did “sensational” business, thanks to Friedlander, earning $7,000 in its first week; a month later the film was still running at the giant Fox theater in Brooklyn.

However, reviews in the New York Times in February and Variety in September were tepid. The Times reviewer wrote: “Despite the Hollywood influence said to have been exercised by Columbia Pictures upon ‘Maria Elena’ […] the ending of this sad story of an innocent maiden's infatuation is just what patrons of importations from below the Rio Grande are accustomed to.” Variety noted: “Entire cast looks like a flock of entertainers gleaned from a better-class nitery.” That was probably closer to the truth than the posters advertising a “native cast,” thereby promising ethnographic eye candy.

Previous to UCLA Film & Television Archive’s restoration by preservationist Miki Shannon, She-Devil Island had been unavailable for decades. The only known nitrate was a three-reel fragment at the Library of Congress. The Archive had an old, complete acetate print in the Richard A. Schwarz Film Collection, then received a second, more or less complete print from Deluxe labs. All of the materials had developing issues from the 1936 release; there were numerous splices, missing footage/jump cuts, severe abrasions, scratches, cinch marks, and the sound was awful. Deluxe’s print was the best looking, but suffered from vinegar syndrome, so a dupe negative was made from that print. Then, damaged sections were replaced with material from the surviving nitrate reels and the Archive print. The sound was rerecorded and cleaned up by John Polito at Audio Mechanics from the surviving prints, so that we now have a beautiful new 35mm print with good sound to highlight the film’s many musical numbers.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation