Yesterday Girl (1966)

The year 1966 was a turning point for German cinema in both East and West Germany. In the Bundesrepublik (Federal Republic), a group of young filmmakers who had made waves three years earlier at the Oberhausen Film Festival by declaring “Papa’s Kino is dead,” presented their first feature films, winning international prizes: Alexander Kluge’s Abschied von gestern [Yesterday Girl] at Venice, Volker Schlöndorff’s Young Törless at Cannes, Peter Schamoni’s Schonzeit für Füchse [Closed Season for Foxes] at Berlin, and Ulrich Schamoni’s Es [It], a German National Film Prize. Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Werner Herzog also completed their first short films, with Wim Wenders following suit a year later. Meanwhile, in the former Deutsche Demokratische Republik (German Democratic Republic), the Communist Party’s Central Committee banned or shelved more than half of the year’s feature films, bringing to a crashing halt a period of liberalization which had encouraged filmmakers behind the wall to tackle humanistic themes and more experimental modes of address than the official aesthetic of Socialist Realism had previously allowed. Now 50 years later, the Berlinale Retrospective program, under the leadership of the Deutsche Kinemathek, has made this yin and yang phenomenon the theme of their program, discovering surprising parallels, in spite of competing ideologies.

One commonality was a generational shift, which saw the cohort of filmmakers that had been trained during the Nazi era and dominated postwar German cinema, on both sides of the wall, move off center stage. The Oberhausen group, which included some of the above named, as well as Edgar Reitz, Haro Senft, Hansjürgen Pohland and others, had published their manifesto, because the West German film industry was dominated by former Nazis, producing UFA-style genre films, while a postwar generation influenced by neorealism and the French New Wave had been left out in the cold. Likewise, East German directors Jürgen Böttcher, Frank Vogel, Frank Beyer, Konrad Wolf and Egon Günther, had all come of age in the 1950s and were looking to move beyond the rigid communist propaganda that had kept GDR audiences away from the cinema in droves. Not surprisingly, then, the generational conflict became the major theme in East and West, as the curators Connie Betz, Julia Pattis and Rainer Rother note in their introduction to the catalog, Deutschland 1966. Filmische perspektiven in ost und west. Indeed, the translated German title for Kluge’s first feature seems programmatic: Good-Bye to Yesterday.

Born in '45 (1966)

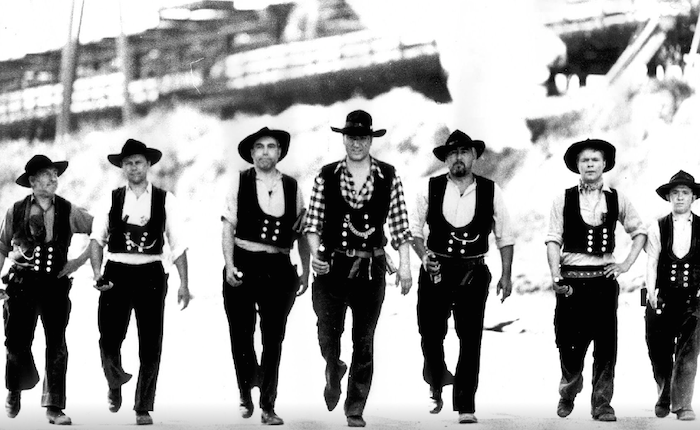

Far from being revolutionary, East German filmmakers attempted (unsuccessfully) to reform the system from within: Jürgen Böttcher’s neorealist-inspired, largely plotless Jahrgang ’45 [Born in ’45] (1966) follows a young East German couple who, though freshly married, are on the brink of splitting up because the husband seems to be searching for something he can’t name, plagued by a vague dissatisfaction with the orderly path society has laid out for him. In Frank Beyer’s brilliant Spur der Steine [Trace of Stones] (1966), a young Socialist construction brigade – with a nod to The Magnificent Seven (1960) – repeatedly circumvents long-entrenched Communist bureaucrats to get the job done and are punished for their efficiency. In Heiner Carow’s Die Reise nach Sundevit [The Journey to Sundevit] (1966), a 10-year-old experiences the hypocrisy and dishonesty of the adult world as he tries to find his friends on the way to summer camp. However, even measured, positive criticism of East German society was too much for Party conservatives, who slapped down the films and filmmakers.

Trace of Stones (1966)

Meanwhile, West German filmmakers visualized the hollowness of the post-WWII economic miracle, constructed by the generation that had been responsible for the Holocaust: although taking place during the Nazi era, Hansjürgen Pohland’s adaptation of Günter Grass’s novel Katz und Maus [Cat and Mouse] (1966) portrays a young non-conformist (provocatively played by Willi Brandt’s sons) who dares to “desecrate” the Iron Cross. In Schonzeit für Füchse [Closed Season for Foxes] (1966), an upper-class German 20-something vacillates between rebellion and resignation in the face of his father, a former Nazi played by Willy Birgel, one of the biggest stars in the Third Reich. In Roland Klick’s Jimmy Orpheus (1966), a young man drifts through nighttime Hamburg, ostensibly chasing a girl he wants to bed, but essentially at sea. In Haro Senft’s Der sanfte Lauf [The Easy Way Out] (1966), a young engineer is alienated from his boss and future father-in-law, but can’t make up his mind to break free. All of the films are characterized by a sense of ennui, of unfocused rebellion against their Nazi-tainted parents, but it would take the events of 1968 to focus German youth on a real political revolution.

Cat and Maus (1966)

Interestingly, these German films from both East and West eschewed the generic formulas and classical narrative strategies of their predecessors. Instead, they shot in real locations, privileging new postwar cityscapes, utilized young, fresh actors, intermingled documentary and fictional forms, dreams and reality, played with cinematic time, employed discontinuous editing and jump cuts, and thus presented viewers more open-ended narratives, rather than spoon-feeding them ideology. While in East Germany, the Party’s reactionary wing under Erich Honecker squelched all liberal reforms, leading to two more decades of Stalinist rule, West Germany would see the ascendency of Social Democracy and the international recognition of New German Cinema.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation