And When I Die I Won’t Stay Dead (2015)

On January 11, I attended the U.S. premiere of two new films by L.A. Rebellion member, Billy Woodberry, at REDCAT in Los Angeles: a short, Marseille après la guerre (2015) and a documentary feature film, And When I Die I Won’t Stay Dead (2015). Having just won an award at Doclisboa International Film Festival in Portugal, the latter film sold out, while crowds still waited in line. It was a great moment for Billy, who recently retired from UCLA, and whose masterpiece, Bless Their Little Hearts (1984), was named to the National Registry in 2013.

I first met Billy 31 years ago at the Berlin Film Festival, when he showed Bless Their Little Hearts in the “Forum of Young Cinema,” at a screening with over 1,000 people in attendance. I had just been hired as Associate Curator of Film at the George Eastman Museum, so I invited Billy to show the film in Rochester, where, as it turned, out he had relatives. After the screening we stayed in touch, but became closer once I started teaching at UCLA 15 years ago. When the Archive organized our L.A. Rebellion program in 2011, Billy was an important contact who occasionally advised me on matters of group dynamics. I also discussed film projects with him. In, I fact had seen a rough cut of And When I Die…, but was surprised by how much the film had evolved into a unified work.

Woodberry’s ten-minute short, Marseille après la guerre is a poetic, black-and-white portrait of dock workers in post-WWII Marseille, which is also an homage to the great Senegalese film director, Ousmane Sembène. Researching the history of the National Maritime Union several years ago, a radical union of sailors founded in 1937, Billy discovered a collection of photographs by union photographers of the docks in Marseille, many portraying dock workers of African descent. The images reminded Billy of Sembène’s book, Le docker noir (The Black Docker; Paris: Debresse, 1956), hence the film. Although the photographs are static, Billy’s framing and editing creates a moving visual narrative, undergirded by the atmospheric Marseille music of Moussu T e lei Jovents.

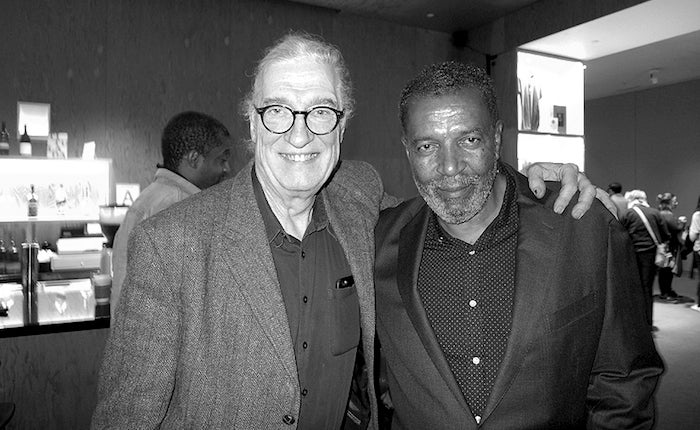

Jan-Christopher Horak with filmmaker Billy Woodberry at REDCAT. Photo courtesy of Harry Gamboa, Jr.

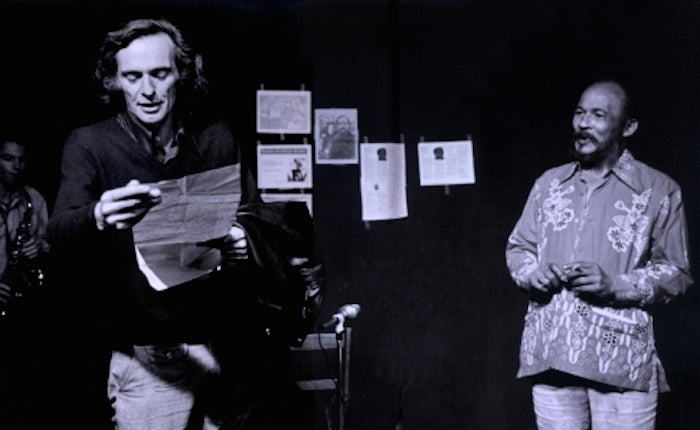

A keen eye for composition and the ability to edit found footage as if it were part of a narrative fiction feature also characterizes Billy Woodberry’s documentary on the African-American beat poet, Bob Kaufman (1925-1986). Considered “the American Rimbaud,” who may have actually coined the term “beatnik,” Kaufman published seven acclaimed books of poetry, including Abomunist Manifesto (San Francisco: City Lights, 1958) and Solitudes Crowded with Loneliness (New York: New Directions, 1965). He was a contemporary of beat poets Jack Kerouac, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, A.D. Winans and Allen Ginsburg, but had been unjustly excluded from the canon, because of his color, as Woodberry speculates. Another reason may have been, as the film demonstrates, that Kaufman slipped in and out of coherence, homelessness, and drug addiction in his later years; indeed, his poems would have been lost, since Kaufman worked in the oral tradition, had his wife Eileen not written them down.

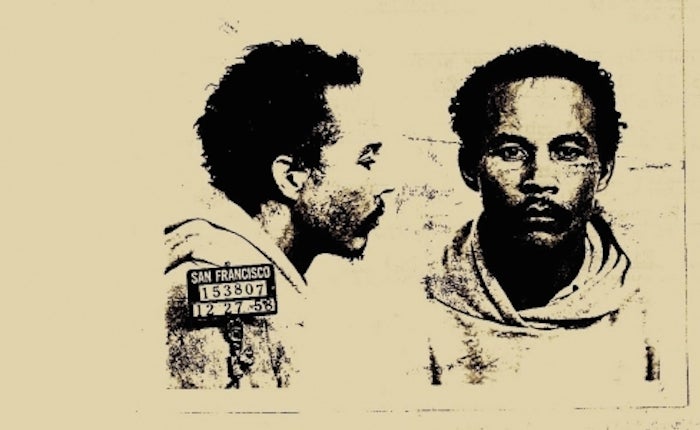

Police and FBI harassment of Kaufman had started years before he was arrested in New York City in the early 1960s, and he was subjected to electric shock treatments at Bellevue Hospital. Kaufman had in fact been a merchant marine during WWII and a union organizer for the National Maritime Union in the 1940s. But in the anti-Communist witch hunts of the post-WWII period, he was expelled from the union, barred from being near any U.S. port, and under constant FBI surveillance. Even after Kaufman moved to North Beach in San Francisco, and started composing poetry, he remained true to his radical politics.

In documenting Kaufman’s life, Woodberry creates an amazing montage of interviews with contemporaries (A.D. Winans, Eileen Kaufman, etc.), documentary and found footage, and photographs, while actors Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee and Roscoe Lee Browne read Kaufman’s poetry, and Charles Mingus and other jazz greats play on the soundtrack. It is a narrative that captures the free-wheeling aesthetics of the beats, and government repression of radical politics through the biography of an African American, who remained outside in more ways than one. I particularly liked the way Woodberry reedited footage from Ron Rice’s The Flower Thief (1960), in which Kaufman had a tiny role, but also the way the film ends with us finally hearing Bob Kaufman in his own words as he recites “Will You Wear My Eyes?” This film deserves to be discovered, for its subject, but also for its poetry and notion that art and radical politics are not incompatible.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation