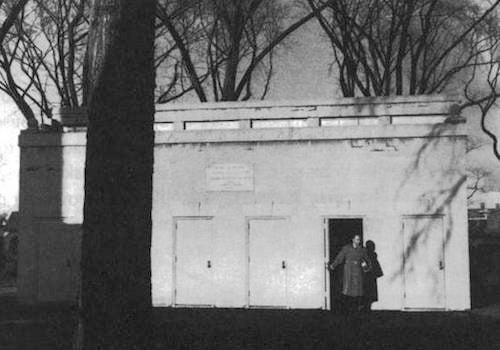

George Eastman Museum original nitrate vaults

40 years ago I began my career as a motion picture archivist, although at the time I don’t think I knew that was actually happening. In September 1975, I moved to Rochester, New York, and began a one-year postgraduate internship in the film department at George Eastman Museum (formerly George Eastman House), funded by the National Endowment for the Arts. As far as I can tell, it was the first formal moving image archive training program in the United States. Getting the internship was more luck than anything else.

I had finished my master’s degree at Boston University in May that year, having written a thesis on “Ernst Lubitsch and the Rise of UFA.” Wishing to continue academic work on German cinema, I applied for and received a fellowship from the Louis B. Mayer Foundation Oral History Program at the American Film Institute, in order to interview German Jewish refugees from the film industry who had fled Hitler after 1933 and ended up in Hollywood. So in June I flew out to California for the first time to conduct a series of oral histories.

While I was doing research at the AFI’s old Greystone Mansion, I got a call from George Eastman Museum, asking me if I would like to have a paid internship in their film department for the next year. Apparently, they had gone through an extensive application process and awarded a candidate, who at the last minute before he was to arrive in Rochester, changed his mind and went to Washington, D.C. instead. When I asked how they heard about me, I was told that they had called my thesis advisor at Boston University, Prof. Evan Cameron, because he had organized a major film conference at Eastman Museum a year earlier. Just the previous semester, I had written a paper about nitrate film preservation for Evan in a seminar on “Theory of Film Production,” after I had told him I wanted to be a film historian or critic, not a filmmaker. In any case, he suggested me to Eastman Museum, and suddenly I had my first archival job.

George Eastman Museum (Image credit: George Eastman Museum)

The film department at Eastman Museum was then still run by legendary film collector and archivist, James Card, who immediately took a liking to me, because he had studied in Germany and was an incurable Germanophile. Unfortunately, Jim was also unavailable most of the time, except when he came in to teach his class. I worked mostly with George Pratt, Marshall Deutelbaum, who eventually moved to a professorship in film studies at Purdue, and Kay McRae, Card’s longtime secretary who assisted me 10 years later when I returned to Eastman House in 1984 as Associate Curator. Ed Stratman, Allan Bobey and projectionist Bob Ogie rounded out the tiny staff.

My first job at Eastman Museum that September was conducting an inventory of the nitrate vaults at the back of the property. I think I spent three months in those vaults with Jonathan Doherty, the son of museum director Robert Doherty, diligently writing down all the information on every can. We had absolutely no training on the handling of nitrate film and working in the old nitrate vaults; unthinkable today, given the many hazards to which we were exposed.

James Card (Image credit: George Eastman Museum)

The irony was that Jim Card was dead set against any kind of cataloguing or inventory. This was an era when the FBI was still looking for film pirates, and many of the films in the archive (as in every major American archive) were there semi-legally, often having been procured in the collector’s market. Card therefore went back into the vaults on weekends, after we had done our inventory, and started moving cans around, so that they could not be found. The museum was never inspected, but for years after I assumed directorship of the archive, we were still trying to remarry prints that had been split apart into different locations in the above exercise.

As an intern, I was involved in almost all departmental activities, including preservation and programming, and learned mostly by doing. I also spent almost all of my free time watching films from the vaults. My whole sense of film history changed. Like most film students, I had a “greatest hits” notion of film history, meaning I had seen some of the classics from Griffith to Fellini, but now I was getting a vertical, as well as a horizontal view of film history. Not just Griffith, but numerous films by his contemporaries, like John Collins, Cecil B. DeMille, Maurice Tourneur; so many treasures, so much to discover. The feeling that I was in a candy store with no house detective in sight has never left me and is one reason I have always been passionate about my work. On weekends I would often project for friends of Card who had come to see films or do research.

By the time I left Eastman Museum, I was pretty sure I wanted to work in an archive, but there weren’t really any jobs back then in the field. I went to Europe, and eventually started a Ph.D., while occasionally doing freelance work as an archive researcher. It was not until eight years later that I returned to Rochester, Eastman Museum and a career as a film archivist. I’ve felt privileged ever since.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation