Images courtesy of Schulberg Productions

Images courtesy of Schulberg Productions

This week marked the 70th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz concentration camp by Soviet forces, the epicenter of the Nazis’ war against the Jews. Coincidentally, I have been watching Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today [Nürnberg und seine Lehre] (1948), made in the wake of the first Nuremberg war crimes trials by Stuart Schulberg for the U.S. Army. The film turns out to be the mother of all Holocaust documentaries, many of its images becoming emblematic representations of the Shoah through their continual repetition in subsequent documentaries. Suppressed after an initial release in Germany, and never shown theatrically in the United States, the film soon disappeared. Sandra Schulberg, the filmmaker’s daughter, has now restored the film (with Josh Waletzky) and released it in a DVD/Blu-ray set including other early Holocaust documentaries and an excellent monograph on the history of the production.

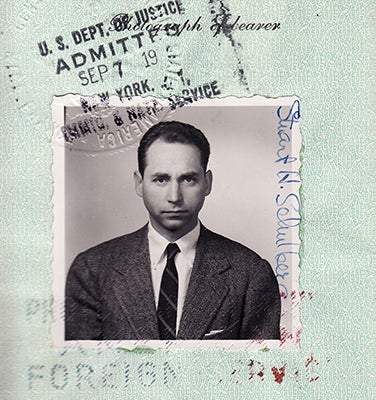

Ms. Schulberg begins by relating the tortured history of the production, which involved an epic three year battle between the War Department’s Film, Theatre and Music Section under Pare Lorentz (the director of the documentary The River), which planned a film that could justify the trials to an international audience, and the film officers at the Office of Military Government, United States (OMGUS) in Germany, which saw the film primarily as a tool for reeducation/denazification of the Germans. Budd and Stuart Schulberg (sons of the legendary B.P. Schulberg at Paramount), who had been serving in the armed forces, were hired by the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) as early as spring of 1945. Under the direction of Navy Commander John Ford, their task was to locate film footage of Nazi atrocities, since the lead American prosecutor, American Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson, had made the revolutionary decision to utilize photographs and films as evidence to convict the Nazi war criminals.

Ms. Schulberg begins by relating the tortured history of the production, which involved an epic three year battle between the War Department’s Film, Theatre and Music Section under Pare Lorentz (the director of the documentary The River), which planned a film that could justify the trials to an international audience, and the film officers at the Office of Military Government, United States (OMGUS) in Germany, which saw the film primarily as a tool for reeducation/denazification of the Germans. Budd and Stuart Schulberg (sons of the legendary B.P. Schulberg at Paramount), who had been serving in the armed forces, were hired by the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) as early as spring of 1945. Under the direction of Navy Commander John Ford, their task was to locate film footage of Nazi atrocities, since the lead American prosecutor, American Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson, had made the revolutionary decision to utilize photographs and films as evidence to convict the Nazi war criminals.

While Budd combed through Nazi footage confiscated by the American government before the war, Stuart searched German archives, only to find that Nazi sympathizers were repeatedly torching film vaults days before the Americans arrived. Scrambling to find visual evidence before the trial commenced on November 15, 1945, despite sabotage and Army SNAFUs, the OSS team was able to put together two films to be shown at the trial. Nazi Concentration Camps (1945), shown on Nov. 29 and The Nazi Plan (1945), shown on Dec. 11, were augmented by The Death Mills (1946, Hanus Burger for OMGUS), and Atrocities Committed by the German Fascists in the USSR (1945, Roman Karmen), the latter presented by the Soviet prosecutor. All four films are extras available on the Blu-ray.

The verdict was announced on October 1, 1946 with 12 defendants receiving death sentences, seven long jail terms and three acquitted. U.S. Signal Corps cameramen were assigned to document the whole Nuremburg trial on film, but for inexplicable reasons, only 50 hours of film were shot of the nearly yearlong trial. This would prove to be a serious handicap, once the Army gave its bureaucratic go-ahead to actually make a film about the trial.

"Let Nuremberg stand as a warning to all who plan and wage aggressive war."

-- Chief U.S. Prosecutor Robert H. Jackson

By mid-1946, the Allies had decided to proceed with a film to justify the first trial and subsequent trials (totaling 12 Nuremberg trials from 1946-49), but conflicts over the political purpose, content and aesthetics of the film arose almost immediately between the Allies themselves and within the U.S. Army. While Stuart Schulberg -- Budd had resigned to work on a new novel -- delivered the first draft script of a trial film in December 1946, OMGUS had hired their own scriptwriter, who delivered a script to Pare Lorentz almost simultaneously. The struggle between the Army factions would continue over two years, while Schulberg completed the film. Nürnberg und seine Lehre premiered in Stuttgart in November 1948 (its release was delayed by the Berlin Blockade), then went into general release the following January, proving to be an unexpected success with German audiences. According to one report, the film “tells the Germans more about Nazism in 80 minutes that we’ve been able to tell them in three years” (p. 45). Shockingly, however, the Army suppressed the film in the United States, possibly because by 1949 the Cold War was in full swing; the government was more interested in hunting Communists than Nazis, and the Germans were suddenly our trusted allies in that fight. The film has in fact never been released until recently.

Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today structures the narrative of the trial around the four counts of the indictment (Conspiracy, Crimes Against Peace, War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity), methodically presenting visual evidence, while simultaneously presenting a moving image history of Nazi Party leaders and their implication in war and genocide. The documentary concludes with trial sentencing and aftermath.

Ironically, even though only a fraction of the film visualizes the Nazi genocide of Jews, many of its images would become emblematic as signifiers of the Holocaust: the book burnings, “Achtung Juden” painted on a shop window, small children behind barbed wire showing their tattoos, mountains of shoes and suitcases, a woman’s emaciated corpse being dropped into a ditch by uniformed Wehrmacht. It is their scarcity that made them so. Except for amateur and illegal footage shot in Holland and the Soviet Union, few other moving image documents of the Holocaust have surfaced since the Schulberg brothers’ search.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation