I first went to the Hollywood Costume exhibition last October for the members opening, then made a second trip in November, because this show so large and dense that it warrants more than one viewing. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) is hosting the exhibition in their temporary space in the May Company building in Los Angeles after its initial run at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. It is also a must-see for anyone interested in Hollywood history. Curated by my colleague at the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television, Deborah Nadoolman Landis, the exhibition is both a survey of Hollywood costumes over the past 100 years and an analysis of the role of costumes in Hollywood filmmaking.

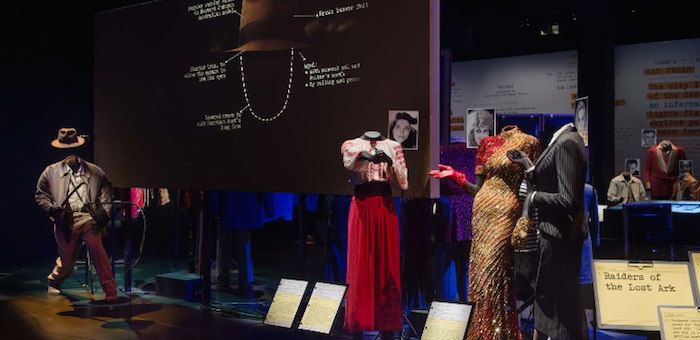

The first and most striking element of the exhibition is its untraditional design and use of new technologies. One enters a completely darkened space, where a whole battery of Oscars for costume design is lighted in a discreet case in the wall, while music is piped in. Divided into three “acts,” the exhibit’s “Act 1 Deconstruction” asks: what is costume design? We see digitized scripts which highlight descriptions of characters to visualize how costume designers plan their work. A designer’s work table is transformed into a screen where we view the various steps a costume designer goes through to begin the design process. “Act II Dialogue” is about “Creative Collaborations” and features video footage, interviewing famous director-costume designer collaborators -- including Martin Scorsese and Sandy Powell, Quentin Tarantino and Sharen Davis, and Tim Burton and Colleen Atwood --, each speaker with his own monitor, appearing as if the pair was in dialogue. "Act II" also covers “Creative Contexts,” in other words, the influence that censorship, the coming of sound, the CGI revolution and other phenomena have had on costume design. “Act III Finale” functions as an apotheosis with a cornucopia of costumes and appropriate film scenes.

As this brief description already indicates, curator Deborah Nadoolman Landis is not just interested in displaying original Hollywood costumes, but also in visualizing the actual work of costume designers. As she notes in her catalog, Hollywood Costume (Abrams Books, 2013), previous Hollywood costume exhibitions often did not even list the costume designer on their labels, while the curator here demonstrates that costumes are an integral part of creating a credible character and mood for the film’s narrative.

Logistically, the exhibition must have been a nightmare. Looking at the labels (presented as film clapboards), I was particularly interested in the lenders, of which there were no less than 60. Just the paperwork alone must have been staggering, given the difficult negotiations with bureaucratic public museums, private studio archives and finicky costume collectors. As one AMPAS insider told me, a number of costumes did not make the transition from London to L.A., due to the above difficulties. On the other hand, a significant number of costumes were added for the L.A. iteration.

Images courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

The exhibition is accompanied by the beautifully illustrated catalog, edited by Landis with contributions by David Robinson, John Landis, Edward Maeder, Valerie Steele, Peter Biskind, Christopher Frayling, Keith Lodwick, Debbie Reynolds and many others. Deborah Nadoolman Landis starts the proceedings with a history of Hollywood costume design. She argues that in the early history of the film medium, as well as in the era of independent production, actors often wore their own clothes if the film was set in contemporary life, leading many producers to think that the role of the costume designer was not really important. Landis counters: “Nothing that appears on screen is casual or accidental -- every single accessory and costume is a deliberate choice made by the designer and, ultimately, the director” (p. 51). Underscoring that notion is Aileen Ribeiro’s extremely illuminating essay on William Hogarth’s series of six paintings, Marriage A-la-Mode (c. 1743), which narrativizes an upper class marriage through the iconography of clothing. Historical costumes for film, on the other hand, while subject to exhaustive research for accuracy, were never completely accurate, but rather designed to conform to modern aesthetic style by way of the silhouette. Or as Maeder writes about Hollywood and history, “the quest for authenticity must be tempered by the expectations and acceptance of the audience” (p. 127).

One of my favorite sections of the catalog discusses the organization of the exhibition itself, especially the wrangling of the costume collectors. Having curated film exhibitions for years with materials from collectors, I can appreciate the negotiation skills that are necessary. Landis is in fact very polite about the whole subject, including the break-up and sale of the famous Debbie Reynolds costume collection, while downplaying their peccadilloes and the fact that exhibitons like this one create value for collectors.

My only minor reservation about the whole undertaking is that the authors, who are mostly industry practitioners, make many proscriptive statements about costume design, which remain theoretically unreflected. Rather than describing Hollywood costume design as a particular aesthetic practice -- based on Hollywood’s (almost never overtly articulated) realist theories of storytelling -- the authors assume the universality of their design theories, even for avant-garde and European art films, in which costumes may in fact be designed for spectacle, regardless of story.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation