For a long time, I considered coffee table style books filled with film posters to be firmly in the category of film buff publications with only limited value to academics. However, while writing my book on graphic designer Saul Bass, I was grateful for such publications because the illustrations alone helped me identify and analyze Bass’ poster art. Many film poster books are still in the nostalgia category, but some do take their role as documents more seriously.

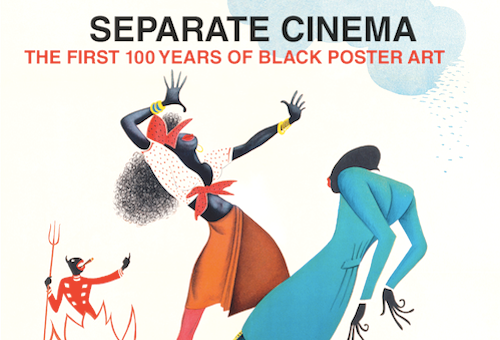

Recently, Separate Cinema: The First 100 Years of Black Poster Art (New York: Reel Art Press, 2014) landed on my desk, a revised and greatly expanded version of A Separate Cinema: Fifty Years of Black Cast Posters. I have long used the 1992 edition, which was co-authored by John Duke Kisch and Edward Mapp with an introduction by black film historian Donald Bogle. Kisch and Mapp are poster collectors, and this publication helped publicize their collections (and create market value for them). Bogle’s essay is a brief history of so-called race films (including those by Norman Film Co. and Oscar Micheaux) and Hollywood’s depiction of African Americans, while the poster illustrations are accompanied by brief synopses of the films. The book is divided into 14  chapters, which break down the material according to content rather impressionistically, as the titles indicate: “Harlem Goes West,” “Jazzin’, Jammin’, and Jivin’,” “African Afrocity,” etc. However, not much is said about the posters themselves, other than reproducing them; a problem I’ve had with a lot of these kinds of publications.

chapters, which break down the material according to content rather impressionistically, as the titles indicate: “Harlem Goes West,” “Jazzin’, Jammin’, and Jivin’,” “African Afrocity,” etc. However, not much is said about the posters themselves, other than reproducing them; a problem I’ve had with a lot of these kinds of publications.

The latest version at least partially corrects that omission by listing the captions separately at the back and including size, origin and the name of the designer, when available. The book is also more than 150 pages longer, expanding – as the title indicates – to cover 100 years of black cinema from The Birth of a Nation (1915) to 12 Years a Slave (2013). The Bogle text and Mapp name have been dropped, with Kisch and British poster dealer Tony Nourmand now responsible for the editing, while Kisch and Peter Doggett (among others) are credited for the texts. As Michael Simmons tells us, Kisch’s Separate Cinema Archive now contains more than 38,000 photos and posters, the largest such collection in private hands. Indeed, despite all the film historical trappings, the primary purpose of the book remains, namely to highlight Kisch’s collection, a fact indicated by the book’s structure.

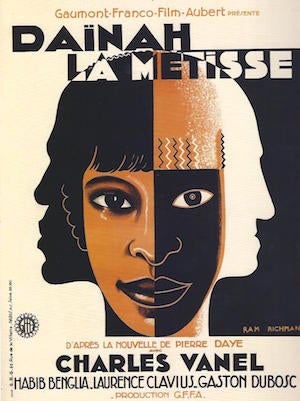

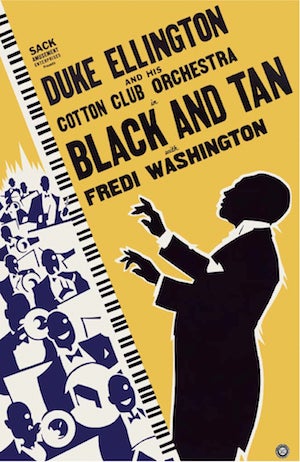

The book includes a new foreword by African American cultural historian Henry Louis Gates, Jr., which functions similarly to Bogle’s text by offering a survey of black film history, but more telescoped. Gates jumps from Griffith to Micheaux to Poitier to blaxploitation to today, devoting not more than two paragraphs for each stop, whereas Bogle writes more extensively about Hollywood’s racial stereotypes  in the classical era (as he did in his book, Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies & Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Films (1973)). On the other hand, the new edition offers much more text in the individual sub-chapters, of which there are now 56. These headings break down as follows: 28 name individuals (Josephine Baker, Quentin Tarantino), eight concern films (The Green Pastures (1936), Carmen Jones (1954)), 10 describe topics (blackface, the urban experience), five are devoted to groups (Norman Film Co., the Polish School) and five to genres (race films, blaxploitation). As these few examples already indicate, the headings remain impressionistic, ahistorical, and are not meant to construct any kind of taxonomy, especially since most categories overlap. For example, Polish posters appear throughout, not just in their own dedicated chapter. Some chapters number as many as 17 pages (“Jazz on Film”), while others are merely two pages (Lena Horne). The inclusion of posters from at least 11 different countries/cultures also makes it difficult to extrapolate any information regarding racial stereotypes or other forms of social history. On the other hand, from the point of view of innovative poster design, the foreign posters are far more interesting than the mostly pedestrian styles of the American work. In other words, this book is of little use as either theory or history, but of great value as art object and Kaffeeklatsch.

in the classical era (as he did in his book, Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies & Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Films (1973)). On the other hand, the new edition offers much more text in the individual sub-chapters, of which there are now 56. These headings break down as follows: 28 name individuals (Josephine Baker, Quentin Tarantino), eight concern films (The Green Pastures (1936), Carmen Jones (1954)), 10 describe topics (blackface, the urban experience), five are devoted to groups (Norman Film Co., the Polish School) and five to genres (race films, blaxploitation). As these few examples already indicate, the headings remain impressionistic, ahistorical, and are not meant to construct any kind of taxonomy, especially since most categories overlap. For example, Polish posters appear throughout, not just in their own dedicated chapter. Some chapters number as many as 17 pages (“Jazz on Film”), while others are merely two pages (Lena Horne). The inclusion of posters from at least 11 different countries/cultures also makes it difficult to extrapolate any information regarding racial stereotypes or other forms of social history. On the other hand, from the point of view of innovative poster design, the foreign posters are far more interesting than the mostly pedestrian styles of the American work. In other words, this book is of little use as either theory or history, but of great value as art object and Kaffeeklatsch.

The book reprints 300 rarely seen photos and posters, which can make for endless conversation. In some cases, the editors have presented several posters from the same film, allowing a comparison between countries of origin (Porgy and Bess (1959)) or distributors (The Exile (1947)). Most of the images are reproduced in full color, printing and paper being of the highest quality. So, while this book is not for everyone, it will be a must for film poster collectors and film historians specializing in black film and in need of visual documentation.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation