A couple of weeks ago I introduced Fritz Lang’s Hangmen Also Die! (1943) at the Skirball Cultural Center, a film I’ve written about extensively. Hangmen was one of the many films made in Hollywood by German émigrés to educate the American public about the anti-Nazi resistance in occupied Europe. In a highly fictionalized manner, it portrayed the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich, the Reichsprotektor ("Reich protector") of Bohemia-Moravia, in May 1942, the resistance of the Czech people against the occupation, and the threat of violence for those who refused to collaborate. The assassination and its horrific consequences—the destruction and mass murder of the Bohemian village of Lidice—were widely reported in the American mass media. However, the actual reality of the “execution” by Czech parachutists from London, working for the government in exile of Edvard Beneš, was not revealed until after World War II. In the film, there is a character named Jan Horak (Dennis O’Keefe), who is the fiancé of the heroine, but that is not my only connection to the film’s events.

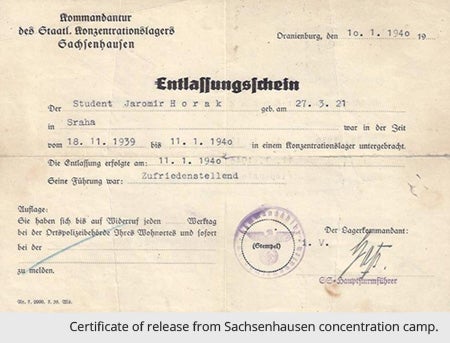

On November 17, 1939, exactly 75 years to the day this week, my dad, Jaromir (Jerome) V. Horak, was arrested by the Gestapo and sent to Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg, a Nazi concentration camp outside Berlin. At the time, he was 19 years old and in his first semester at the Technical University in Prague. It had been eight months since the Germans had invaded Czechoslovakia on March 15, taking the country essentially without a fight. The French and British had signed the Munich Agreement in September 1938, ceding the so-called Sudetenland (the Republic’s mountainous natural borders) to Hitler, and making any armed resistance futile. On November 15, thousands of Czech students flooded the streets of Prague to accompany the funeral of Jan Opletal, a medical student who had been shot by the Nazis during demonstrations on October 28, Czechoslovak Independence Day.

Two days after the funeral march, Hitler himself ordered that Czech institutions of higher learning be closed for three years. The Gestapo came to my grandparents’ home in Prague-Vysočany shortly after 5 p.m. and took their son downtown to their headquarters in the Petschek Palace, where nine students and professors were immediately executed without trial. More than 1,200 other students were also arrested and sent to concentration camps. Ironically, my dad had not participated in any demonstrations, but was probably arrested because my grandfather was general director of ČKD (Českomoravská Kolben-Daněk), the country’s largest manufacturer of motorcycles, locomotives and tanks; in other words, armaments the Germans needed for their war plans. Worried about sabotage and work slow-downs, the Nazis probably believed they could keep the Czech ruling class in check by taking away their children.

Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg had been built by the Nazis in 1936 to incarcerate German political prisoners without due process, including Jews, but it was not an extermination camp. By the time my father entered its gates on November 20, which featured the infamous slogan, “Arbeit macht frei” (“work makes you free”), 12,168 prisoners struggled to survive there under terrible conditions. Fortunately, my dad was suddenly released on January 10, 1940. Six feet tall and weighing only 80 pounds, he made his way to Berlin’s Anhalter train station, where he ate two bowls of pea soup, which he promptly threw up on the train to Prague.

Only when he arrived home was he told that his freedom had been bought. My grandfather had invited Konstantin von Neurath, the first Nazi Reichsprotektor, to the family’s hunting lodge in Řevničov in Western Bohemia, where he agreed to pay a huge ransom to the Nazis. Once my dad had recovered, he joined the Resistance, distributing anti-Nazi leaflets. Resistance and collaboration thus marked my family, as it has virtually all Czechs. But the story doesn’t quite end there.

My father’s uncle, General Josef Kohoutek, was executed at Berlin-Plötzensee on September 19, 1942, in partial retribution for the Heydrich assassination, since he was a ranking officer in Czechoslovak Army Intelligence.  His wife, my great aunt Mila, was awarded a medal after the war, having briefly protected one of the Heydrich assassins. She was then sent to prison for eight years after the Communist Putsch in March 1948, because the new dictatorship denied the existence of a non-Communist resistance against the Nazis. In August 1948, my father, working with the American State Department, organized the spectacular escape of Dr. Petr Zenkl, the leader of the largest opposition party, the Czech National Socialists, who had previously been under house arrest before fleeing to West Germany. Before crossing the border, my father spent the night in my grandfather’s isolated hunting lodge. He would not return home for 17 years, nor would my grandparents know whether he was dead or alive for much of that time.

His wife, my great aunt Mila, was awarded a medal after the war, having briefly protected one of the Heydrich assassins. She was then sent to prison for eight years after the Communist Putsch in March 1948, because the new dictatorship denied the existence of a non-Communist resistance against the Nazis. In August 1948, my father, working with the American State Department, organized the spectacular escape of Dr. Petr Zenkl, the leader of the largest opposition party, the Czech National Socialists, who had previously been under house arrest before fleeing to West Germany. Before crossing the border, my father spent the night in my grandfather’s isolated hunting lodge. He would not return home for 17 years, nor would my grandparents know whether he was dead or alive for much of that time.

In honor of the murdered Czech students, November 17 is now celebrated as International Students’ Day.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation