The German language has a few virtually untranslatable words, often made up of two other words. One of my favorites is Schadenfreude, which means joy at the misery of others. Another is Zerstörungswut, which translates as destroying with anger, but actually means the lust for destruction. If language defines national character, then both of these terms are right on the money. I had to think of the latter term a couple of weeks ago while attending a discussion about the new restoration of The Cabinet  of Caligari (1919) at the Berlin Film Festival, during which it was revealed that the restoration was only made possible because the original camera nitrate negative (OCN) has survived in the former East German Staatliches Filmarchiv der Deutschen Demokratischen Republic. The negative would have been long gone in the Federal Republic, because it is the official policy of the Federal German Archives to destroy all nitrate as soon as it is copied, regardless of its historical value and ignoring the fact that nitrate will last a very long time, if stored properly. I wondered whether the OCN will now be burned after digitization.

of Caligari (1919) at the Berlin Film Festival, during which it was revealed that the restoration was only made possible because the original camera nitrate negative (OCN) has survived in the former East German Staatliches Filmarchiv der Deutschen Demokratischen Republic. The negative would have been long gone in the Federal Republic, because it is the official policy of the Federal German Archives to destroy all nitrate as soon as it is copied, regardless of its historical value and ignoring the fact that nitrate will last a very long time, if stored properly. I wondered whether the OCN will now be burned after digitization.

As I wrote on my Facebook page, I caused a mini scandal at the discussion, because I dared to ask why the Germans spend millions of Euros repeatedly restoring the five great German classics, while literally hundreds of German nitrate prints from the silent era rot in the archives in Germany and abroad. What is this obsession with this handful of canonized works to the detriment of the rest of film history? The short answer was: there is no money for film preservation and no one really cares. But some do care. Below is a petition to the German government, which I had a small hand in translating into English, now signed by more than 4,300 international film academics and artists. If you want to add your name, go to the Filmerbe in Gefahr online petition.

from the silent era rot in the archives in Germany and abroad. What is this obsession with this handful of canonized works to the detriment of the rest of film history? The short answer was: there is no money for film preservation and no one really cares. But some do care. Below is a petition to the German government, which I had a small hand in translating into English, now signed by more than 4,300 international film academics and artists. If you want to add your name, go to the Filmerbe in Gefahr online petition.

The Petition

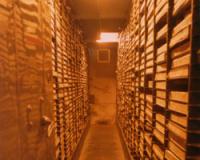

If politicians continue to ignore the advancing chemical decomposition of our collective film patrimony, then, in the coming years, we will have to accept the loss of most films from the last century. Under bureaucratic custody, the priceless analog original negatives and unique prints of our cinema legacy are falling apart silently, without causing a stir, without the benefit of new life. In the “Age of Technical Reproducibility” (Walter Benjamin), it is of all things film art that is in danger of dying, because so much of it can no longer be reproduced.

Apart from the easily flammable nitrate-based celluloid from the first fifty years of cinema, film archives are most worried about those works created on acetate-based safety film, since the 1950s: 35mm feature films, 8mm and 16mm films, photographic negatives, magnetic coated films, microfilms, as well as all negatives and copies in black & white and color. If, as is normally the case, the material is stored in rudimentarily air-conditioned rooms (20º Celsius and 50% humidity), it will only have a guaranteed lifespan of forty-four years. Beyond these values, as established by the Image Permanence Institute (Rochester, N.Y.), begins an unquantifiable risk zone.

The moving image only has one life in its perpetual reproduction. That is its nature. A single analog or digital original film print is always at risk of mechanical or chemical destruction or data loss. We have to think differently: to preserve the moving image means to permanently reproduce it at the highest technical level. That is the only guarantee that it can be anchored in the national memory.

In order to manage the digitization of our film heritage, we propose the creation of a central coordinating board from the Deutsche Kinematheksverbund (German Film Archive Network). Such a board must focus the existing expertise at the German film archives, prepare the digitization and negotiate contract terms with the technically-oriented film and television companies. This daunting task can only be attempted by all the German archives together. Without the close cooperation of still-extant film laboratories and image processing companies, this pending work cannot be accomplished. And when the film expertise to be found there is no longer available, the problem will have solved itself, so to speak.

In order to manage the digitization of our film heritage, we propose the creation of a central coordinating board from the Deutsche Kinematheksverbund (German Film Archive Network). Such a board must focus the existing expertise at the German film archives, prepare the digitization and negotiate contract terms with the technically-oriented film and television companies. This daunting task can only be attempted by all the German archives together. Without the close cooperation of still-extant film laboratories and image processing companies, this pending work cannot be accomplished. And when the film expertise to be found there is no longer available, the problem will have solved itself, so to speak.

For the digitization and copying of its own film heritage, France is spending 400 million euros over the course of six years. In Germany, there is only 2 million euros available annually for a few well-known film titles. In order to avert the pending decline of our film holdings, an investment of approximately 500 million euros by the end of this decade is necessary.

We demand an initiative at the federal level to digitize all endangered film inventories. We expect a reliable and substantial financial commitment from the next federal government. In the future, the preservation of our film patrimony must be a national mission. This moving image legacy must be indelibly secured, in order to remain visible and accessible in the digital age. The Federal government must therefore strengthen the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv (Federal Film Archive) as the nation’s central German film archive, both through direct funding and human resources, while supporting the digitization of our film legacy through the establishment of a permanent Fund. We will watch closely to see whether the respective assurances of the Coalition contract of 26 November 2013 are followed with actual deeds.

Berlin, 26 November 2013

Jeanpaul Goergen (film historian), Prof. Helmut Herbst (filmmaker), Prof. Dr. Klaus Kreimeier (journalist and media studies scholar).

Translated by Jan-Christopher Horak and Evan Torner.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation

Comments