I recently watched My Dinner with Jimi (Bill Fishman, 2003), a great little film about Howard Kaylan and The Turtles that seemingly never got any play when it was released, except at a few film festivals. The title refers to Kaylan’s (Justin Henry) dinner in 1969 in London with Jimi Hendrix (Royale Watkins, who BTW is spot on) and was a nod to Louis Malle’s My Dinner with André (1981). Having graduated from high school in ’69, I thought the film really captured the atmosphere of the period, despite an extremely modest budget, by wisely inserting little-seen historical footage. Lots of other 60s rock stars also make appearances, better said actors playing them, including Mama Cass, Frank Zappa, Graham Nash, the Beatles and the Stones, as well as all the Turtles, today best known for their 1967 monster hit, “Happy Together.” The film was released by Rhino Entertainment, an off-shoot of Rhino Records, which produced a number of films at the turn of the century, including Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998), Why Do Fools Fall in Love (1998)—recently shown at the Billy Wilder Theatre—and Daydream Believers: The Monkees’ Story (2000).

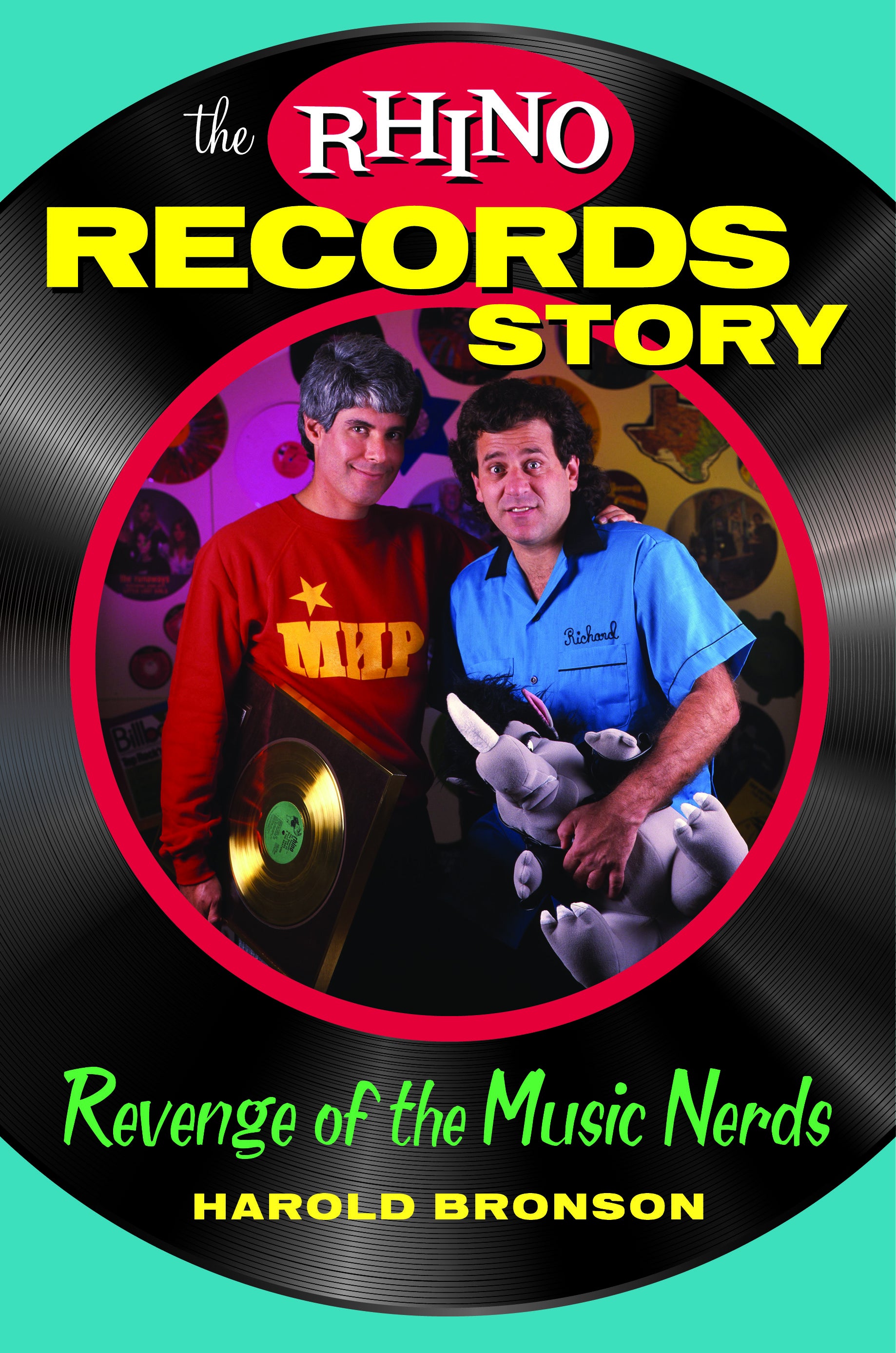

Rhino Records started out in 1973 as a record store on Westwood Boulevard, just blocks from the UCLA campus, then transitioned to a record label, founded in 1978 by Richard Foos (the store’s original owner) and Harold Bronson (the store’s manager since 1974). Rhino specialized in rereleasing out-of-print popular music from the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, as well as novelty and comedy records. Now Harold Bronson has published an autobiography, The Rhino Records Story: Revenge of the Music Nerds (SelectBooks, 2013), which not only details the remarkable growth of this funky little music company, but also gives an insider’s view of how brutal the business we call the recording industry was/is, in the process taking revenge on giants like Warner Bros., which eventually gobbled up, corporatized and homogenized Rhino to the point that it is now indistinguishable from their other corporate entities.

Rhino Records started out in 1973 as a record store on Westwood Boulevard, just blocks from the UCLA campus, then transitioned to a record label, founded in 1978 by Richard Foos (the store’s original owner) and Harold Bronson (the store’s manager since 1974). Rhino specialized in rereleasing out-of-print popular music from the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, as well as novelty and comedy records. Now Harold Bronson has published an autobiography, The Rhino Records Story: Revenge of the Music Nerds (SelectBooks, 2013), which not only details the remarkable growth of this funky little music company, but also gives an insider’s view of how brutal the business we call the recording industry was/is, in the process taking revenge on giants like Warner Bros., which eventually gobbled up, corporatized and homogenized Rhino to the point that it is now indistinguishable from their other corporate entities.

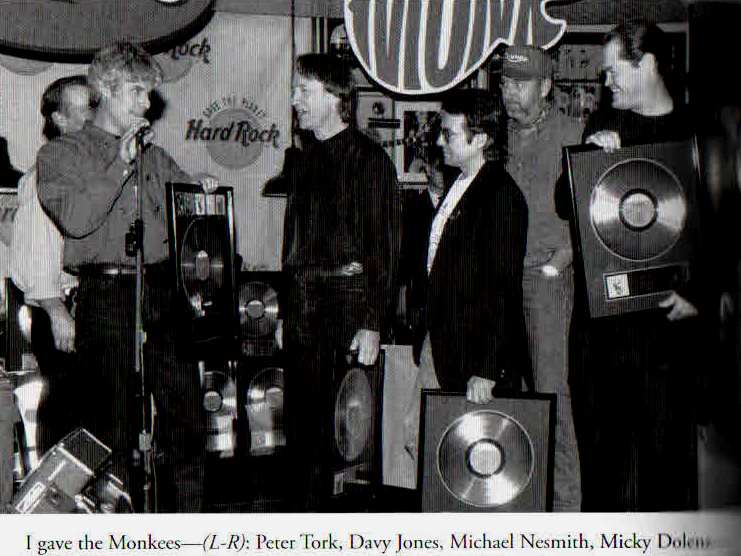

Bronson’s early chapters on “the best damned record store in California” and the beginnings of the Rhino label read a bit like Tom Wolfe’s narrative of Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, with the hippie Foos and self-proclaimed weird music nerd Bronson (a UCLA grad) in it for the comedy and to avoid “real” jobs. Indeed, the duo seemingly rarely made business decisions based on financial logic, and instead produced what they liked with only the thought of making enough money to do it again. Ironically, they became hugely successful, releasing both “old” music (The Turtles, The Monkees, The Box Tops, The Troggs, Spencer Davis Group, Tommy James) and novelty stuff (Temple City Kazoo Orchestra, Big Daddy), while their attempts at competing with the majors on the heavy metal band front were less lucrative.

Despite growing the company from one unpaid employee to a staff of fifty and sales of over $14 million in 1987, Rhino received little respect from the execs at ElectrAtlantiCapitol, whose cocaine budgets in the 80s were probably larger than what Rhino turned over. Rhino did eventually get a distribution deal from Capitol, but they were still treated as bottom feeders, with one company executive quipping that the duo cannibalized the “dreams of other people and other record companies.” Yet when PolyGram realized Rhino had sold 188,000 copies of Village People’s Greatest Hits, they refused to renew the license and put out their own greatest hits album of the group. In fact, Rhino not only resurrected the careers of dozens of recording artists, but also paid them substantial sums, in stark contrast to their original labels, which had usually underreported sales to screw the artists financially. The chapters on The Turtles, The Monkees, and The Knack are especially enlightening in this respect, but Bronson also notes that some artists were not always grateful, despite windfall earnings decades after their last hits.

As noted above, Rhino then expanded into film production and video distribution, specializing in pop and rock music themed films on the production front and novelty items for video, including Battle of the Bombs (1985)(compiling the best scenes from the worst movies), Sleazemania (1985), and a compilation of ABC’s Shindig! Not all of these efforts were successful, but interest in the company continued, leading to a joint venture deal with Atlantic Records in 1992, a subsidiary of Warner Music Group. For most of the 90s, Rhino maintained its independence, but after the AOL/Time Warner merger in 1999, things changed, as corporate executives whittled away at Rhino’s autonomy. Without exactly accusing WMG of anti-Semitism, Bronson does note that by 1999 six music division heads had been replaced by gentiles. By 2001, Bronson’s contract had been terminated, and soon after Foos also left to found Shout! Factory (which has released UCLA Film & Television Archive titles), despite the fact that in 2001 Rhino was the most profitable of all the companies in WMG.

As noted above, Rhino then expanded into film production and video distribution, specializing in pop and rock music themed films on the production front and novelty items for video, including Battle of the Bombs (1985)(compiling the best scenes from the worst movies), Sleazemania (1985), and a compilation of ABC’s Shindig! Not all of these efforts were successful, but interest in the company continued, leading to a joint venture deal with Atlantic Records in 1992, a subsidiary of Warner Music Group. For most of the 90s, Rhino maintained its independence, but after the AOL/Time Warner merger in 1999, things changed, as corporate executives whittled away at Rhino’s autonomy. Without exactly accusing WMG of anti-Semitism, Bronson does note that by 1999 six music division heads had been replaced by gentiles. By 2001, Bronson’s contract had been terminated, and soon after Foos also left to found Shout! Factory (which has released UCLA Film & Television Archive titles), despite the fact that in 2001 Rhino was the most profitable of all the companies in WMG.

Bronson’s book makes extremely lively reading, but there is also an undercurrent of disappointment that bleeds through, as if all the accomplishments are forgotten when one has been put out to pasture. Many of us have had that feeling, working in an industry where youth and inexperience are often prized over long-term commitments.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation