The Mexican cinematographer, Gabriel Figueroa, is revered in his native country as a national treasure, an artist/muralist who chose film as his personal medium of expression. Figueroa was responsible for many of the great films of classical Mexican cinema, whether directed by Fernando de Fuentes, Emilio Fernández, Roberto Gavaldón or Luis Buñuel. He has been richly honored with retrospectives across the world, whether at MOMA or the Munich Film Museum, where we staged a retrospective program in 1994. However, it is good to have “The Golden Age of Mexican Cinema,” a Figueroa series from front to back, now in Los Angeles and running through next weekend.

Staged at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), in conjunction with the exhibition “Under the Mexican Sky: Gabriel Figueroa—Art and Film,” both the exhibition and film program are co-presented with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences. Given that 35mm projection positives are ever harder to find, assistant curator of film programs Bernardo Rondeau has done a fantastic job of sleuthing out good prints, which are being screened at the Bing Theatre.

Opening night, however, was at the Academy’s Samuel Goldwyn Theater, where Mexican-American writer-director Gregory Nava (El Norte, Why Do Fools Fall in Love) presented a lecture, richly illustrated with film clips from Figueroa’s work. Nava discussed Figueroa’s status in Mexico as the country’s "Fourth Muralist," next to painters José Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Diego Rivera, as well as his seminal cinematography which contributed to the establishment of Mexico’s post-revolutionary visual culture and national identity.

Nava’s well chosen clips from María Candelaria (1944), starring Dolores del Rio, Enamorada (1946) with María Félix, La perla (1947, based on John Steinbeck), and Víctimas del pecado (1951) certainly wet my appetite. A panel discussion followed, which included Figueroa’s son, Gabriel Figueroa Flores (himself a cameraman), cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto (Argo), actor Gael García Bernal (Y tu mamá también), and veteran film star, Silvia Pinal (The Exterminating Angel, Viridiana). Pinal, who in the 1950s appeared in films with Tin Tan, Cantinflas and Pedro Infante, and under Bunuel’s direction in the 1960s, is idolized in Mexico as the grand dame of Telenovelas.

Nava’s well chosen clips from María Candelaria (1944), starring Dolores del Rio, Enamorada (1946) with María Félix, La perla (1947, based on John Steinbeck), and Víctimas del pecado (1951) certainly wet my appetite. A panel discussion followed, which included Figueroa’s son, Gabriel Figueroa Flores (himself a cameraman), cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto (Argo), actor Gael García Bernal (Y tu mamá también), and veteran film star, Silvia Pinal (The Exterminating Angel, Viridiana). Pinal, who in the 1950s appeared in films with Tin Tan, Cantinflas and Pedro Infante, and under Bunuel’s direction in the 1960s, is idolized in Mexico as the grand dame of Telenovelas.

This was my first María Félix film and I’m flabbergasted by her screen presence.

The film program opened a day later with one of the strongest titles in the series, Enamorada (1947, Emilio Fernández), in translation “A Woman in Love,” which is a bit of a misnomer, because the film is mostly about a man in love. A loose adaptation of “The Taming of the Shrew,” the film gives a whole new meaning to the Hollywood term, "meet cute." Macho man, and Mexican revolutionary General Reyes (Pedro Armendáriz), conquers the pueblo of Cholula, then falls hopelessly in love with Beatriz Peñafiel, the daughter of the richest and most conservative man in town. Embodied by María Félix, she knocks him off his feet with a slap after he whistles at her, then literally blows him off his horse with a bomb. The “taming” here consists of the General getting down on his knees repeatedly and asking her for forgiveness for all the atrocities he has committed. And she does fall eventually, giving us one of the most ecstatic moments in the history of cinema: An extreme close-up of Beatriz awakening to love, as Reyes serenades her under her window, Figueroa’s camera framing the actress’s eyes in an extreme diagonal close-up. The film ends with Felix joining her lover as he leaves the pueblo for a new campaign, walking beside his horse. As is the custom with women following their men into battle, she holds on to the horses’ tail, a not so subtle sexual innuendo. The final scene shamelessly steals from Joseph von Sternberg’s Morocco (1930), where Marlene Dietrich follows Gary Cooper into the desert as a “campfire girl.” This was my first María Félix film and I’m flabbergasted by her screen presence.

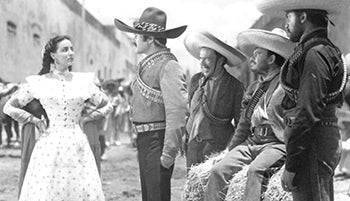

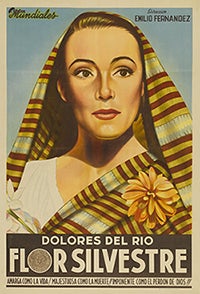

The second feature was Flor Silvestre (Wild Flower) (1943, dir. Emilio Fernández), again featuring Pedro Armendáriz, this time with Dolores del Rio, starring in her first Mexican film after a long career in Hollywood. Armendáriz plays the son of a rich hacienda owner who falls in love with and marries a peasant woman, defying class conventions; he then joins the Mexican revolution, as does she. He eventually sacrifices himself to save his wife and young son, who gets to hear the whole story in flashback from his aging mother, as they look over the rich Mexican land. Like many Mexican films of the classical era, this one celebrates the Mexican revolution with epic landscapes and an uplifting story, but it doesn’t contain any of the ironic fissures that make Fernando de Fuentes’ Vámonos con Pancho Villa! (1936) a more satisfying work. Dolores is every bit the film star, even as she reinvents herself as a campesina, but she was no match for the burning intensity of Maria Félix’s eyes.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation