This week I drove out to Pacific Palisades to the Villa Aurora, the German cultural center, to attend a screening of a new German television documentary, Alexander Granach (2012). I hadn’t been to the Villa since Margaret Kleinman took over the Directorship, having previously spent decades at the L.A. Goethe Institute as a film programmer. Driving from Hollywood, I had forgotten what a long drive down Sunset Boulevard it is to the Villa, which is perched high above the Pacific Ocean.

The Villa Aurora was originally owned by Lion and Marta Feuchtwanger, the German novelist and his wife, who were forced to flee from Hitler and eventually settled here. Unlike many other German Jews who arrived penniless in this country as exiles, Feuchtwanger was relatively affluent, due to the fact that his novels were very popular in English translation in the 1920s and 1930s, although he is largely forgotten today in the Anglo-Saxon sphere. In particular, his novels Jud Süß (1925) and Josephus (1933), were major successes in the United States, the former becoming the basis for both Lothar Mendes’ philo-Semitic British production, Power (1934) and Veit Harlan’s rabidly anti-Semitic Nazi film, Jud Süß (1940).

“When historians go into the archives in 200 years to view films, in order to see what the Nazis looked like, they will discover that the Nazis were a purely Semitic race, as portrayed by Alexander Granach, Martin Kosleck, Ludwig Donath, and many others.” - Alfred Polgar

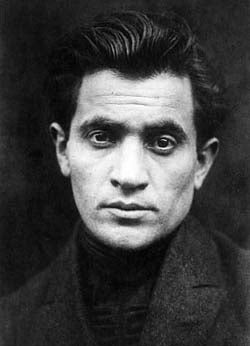

I wanted to see Alexander Granach, because Granach was a subject in my dissertation (Anti-Nazi Films Made in Hollywood by German Jewish Refugees), and I’m one of the interviewees in the film. Like most German speaking Jewish actors who ended up in Hollywood because they were thrown out of the Nazi-German film and theatre industry, Granach appeared in numerous anti-Nazi films, including: So Ends Our Night (1941, John Cromwell), Hangmen Also Die! (1943, Fritz Lang), The Hitler Gang (1944, John Farrow) and The Seventh Cross (1944, Fred Zinnemann). He was most memorable as Gestapo Inspektor Alois Gruber in Hangmen, a no-nonsense character Fritz Lang based on Inspector Lohman (Otto Wernicke) in M (1931). In The Hitler Gang he gave a dead on performance as Julius Streicher, Hitler’s close confidant. The fact that virtually all the Nazis in Hollywood films during World War II were Jewish actors with thick German accents lead to an often repeated anecdote in the Hollywood exile community, which the German writer Alfred Polgar first put to paper: “When historians go into the archives in 200 years to view films, in order to see what the Nazis looked like, they will discover that the Nazis were a purely Semitic race, as portrayed by Alexander Granach, Martin Kosleck, Ludwig Donath, and many others.” As the documentary by Angelika Wittlich makes clear, however, Granach’s story was even more interesting, given that he was not only a victim of German Fascism, but almost disappeared into Stalin’s Gulag in the Soviet purges of the 1930s.

I wanted to see Alexander Granach, because Granach was a subject in my dissertation (Anti-Nazi Films Made in Hollywood by German Jewish Refugees), and I’m one of the interviewees in the film. Like most German speaking Jewish actors who ended up in Hollywood because they were thrown out of the Nazi-German film and theatre industry, Granach appeared in numerous anti-Nazi films, including: So Ends Our Night (1941, John Cromwell), Hangmen Also Die! (1943, Fritz Lang), The Hitler Gang (1944, John Farrow) and The Seventh Cross (1944, Fred Zinnemann). He was most memorable as Gestapo Inspektor Alois Gruber in Hangmen, a no-nonsense character Fritz Lang based on Inspector Lohman (Otto Wernicke) in M (1931). In The Hitler Gang he gave a dead on performance as Julius Streicher, Hitler’s close confidant. The fact that virtually all the Nazis in Hollywood films during World War II were Jewish actors with thick German accents lead to an often repeated anecdote in the Hollywood exile community, which the German writer Alfred Polgar first put to paper: “When historians go into the archives in 200 years to view films, in order to see what the Nazis looked like, they will discover that the Nazis were a purely Semitic race, as portrayed by Alexander Granach, Martin Kosleck, Ludwig Donath, and many others.” As the documentary by Angelika Wittlich makes clear, however, Granach’s story was even more interesting, given that he was not only a victim of German Fascism, but almost disappeared into Stalin’s Gulag in the Soviet purges of the 1930s.

Born in a small town in Galacia (then Austro-Hungary, now the Ukraine), Granach was a multicultural phenomena in and of himself, speaking and acting in Yiddish, Russian, Polish, Ukrainian, and German. By the early 1920s, he was being celebrated as one of the most intense and exciting performers on the German stage in Berlin. Short and stocky, Granach roared as Shylock in Max Reinhardt’s production of “The Merchant of Venice.” Simultaneously, his German film career took off after he appeared as Knock, the bonkers real estate agent in F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922), and culminated with his starring role as one of the miners in G.W. Pabst’s anti-war drama, Kameradschaft (1931). In between, Granach acted in no less than thirty-two German films, a fact the filmmaker glosses over in order to privilege his theatrical acting.

After Hitler came to power, Granach received an invitation to the Soviet Union, where he appeared in a couple films and ran a Yiddish language theatre in Kiev. However, like many German exiles who had fled to the Soviet Union, Granach ultimately found himself first a persona non grata, and then in 1937, he was arrested as a German spy by Stalin’s secret police. It was only the intervention of none other than Lion Feuchtwanger, who personally wrote to Stalin (having visited him during a celebrated tour of the Soviet Union in 1935) that Granach was allowed to exit the country alive, eventually making his way to Hollywood via Switzerland.

Amazingly, Granach immediately landed a plum role as one of the three Russian commissars in Ernst Lubitsch’s Ninotchka (1939), starring Greta Garbo. In yet another irony of history, he was again playing one of his erstwhile persecutors, even though this was a comedy. Afterwards, Granach worked steadily in character parts in Hollywood, but also successfully cracked the Broadway stage with his performance in “A Bell for Adano” (1944). Granach, however, would not live to see the end of Hitler, nor the publication of his very well regarded autobiographical novel, There Goes an Actor (1945), which was published in the year of his death at the age of 51. He died of an embolism following an appendectomy, but it was really years of hardship in exile that killed him.

Amazingly, Granach immediately landed a plum role as one of the three Russian commissars in Ernst Lubitsch’s Ninotchka (1939), starring Greta Garbo. In yet another irony of history, he was again playing one of his erstwhile persecutors, even though this was a comedy. Afterwards, Granach worked steadily in character parts in Hollywood, but also successfully cracked the Broadway stage with his performance in “A Bell for Adano” (1944). Granach, however, would not live to see the end of Hitler, nor the publication of his very well regarded autobiographical novel, There Goes an Actor (1945), which was published in the year of his death at the age of 51. He died of an embolism following an appendectomy, but it was really years of hardship in exile that killed him.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation