Footprints of Pan-Africanism (2017)

When UCLA Film & Television Archive embarked on its massive “L.A. Rebellion” project in 2011, we knew that we were dealing with living and often still working filmmakers, rather than just a phenomenon in film history. Happily, while the Archive has continued to find and restore films by the L.A. Rebellion group, some of the filmmakers have continued to release new work, including Billy Woodberry, Julie Dash, Zeinabu Irene Davis and Shirikiana Aina. Aina's new film, Footprints of Pan-Africanism (2017), focuses on one of the overriding themes of many L.A. Rebellion films, namely the relationship of African-Americans to Africa.

Shirikiana Aina was born in Detroit in 1955 and received her B.A. from Howard University, then attended UCLA, where she earned her M.A. in African Film Studies in 1982 with her thesis film, Brick by Brick (1982), which documented the gentrification of poor African-American neighborhoods in Washington, D.C. in the 1970s. At UCLA, Aina met and eventually married Ethiopia-born filmmaker Haile Gerima, who was both a student of and mentor to younger L.A. Rebellion filmmakers. While working on some of Haile Gerima’s films, including co-producing Sankofa (1993), and raising five children, Aina also completed her feature documentary, Through the Door of No Return (1997). The film recalls her late father’s trip to Africa, which earned him an FBI label as a political radical. In Ghana, she found a fort from which tens of thousands of slaves were shipped to the Americas, also discovering a group of African-Americans living there. It is the story of those emigrants to Ghana that is the focus of her new film.

Footprints of Pan-Africanism begins with the story of a stone belonging to a friend's great grandmother, brought by her enslaved ancestor from West Africa and passed down through generations, a physical connection to their African ancestors. She then cuts to images of the former Gold Coast, renamed Ghana at the moment of its independence on March 6, 1957. Led by Kwame Nkrumah, its first president, Ghana became the first country in Africa to throw off its colonial yoke and the first great experiment in Pan-Africanism, according to Martin Luther King Jr. In pursuit of that goal, Nkrumah not only founded the Organization of African Unity, but also invited Diaspora Africans to Ghana to participate in the project of nation building. By overlaying the images with American jazz, Aina connects African-American culture to the fate of Africa.

Kofi Awoonor in Footprints of Pan-Africanism

Drs. Robert and Sara Lee from South Carolina were among the Americans to heed the call, as were former American Army vets Curtis Kojo Morrow, Carlos Alton and John Ray, whose interviews structure the film. Two other prominent émigrés were the poet Maya Angelou and George Padmore, an American Communist expelled from the U.S., who became one of the architects of Ghana’s Pan-African policies with the formation of the Office of African Affairs. Other interviews with British subject Yvonne Sobers, poet and diplomat Kofi Awoonor (to whom the film is dedicated), Cecile McHardy and Esi Sutherland-Eddy (Director of the W.E.B. DuBois Center in Accra) discuss the excitement many felt participating in this first free African nation. The film makes the point that it was Americans or Africans trained in America, rather than British-allied Ghanians who were the motor for change in the country.

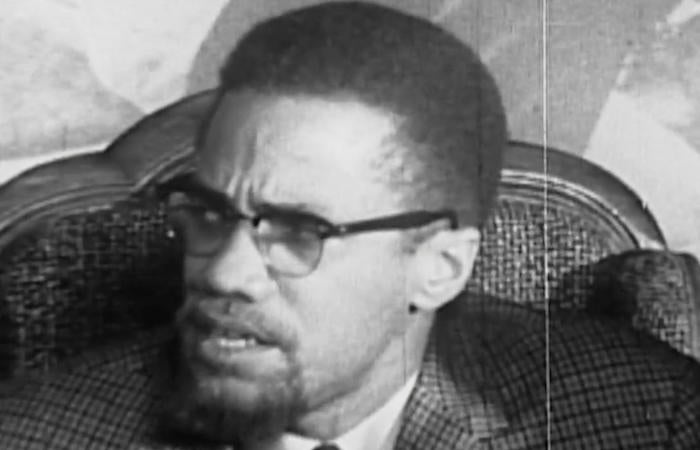

Malcolm X in Footprints of Pan-Africanism

Like so many L.A. Rebellion films, Aina’s Footprints of Pan-Africanism also pays tribute to four African-American leaders who “touched” Ghana: Marcus Garvey, whose program of African-American economic independence heavily influenced Nkrumah when he spent 10 years in the U.S., studying and teaching at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania; W.E.B. Du Bois, who was invited to Ghana by Nkrumah in 1961 to write an encyclopedia of Africana and died there two years later at the age of 96 after becoming a Ghanian citizen; Malcolm X, who visited Ghana in 1964 after his break with the Nation of Islam at a time when he was conceptualizing his own Pan-African political movement; Martin Luther King Jr., who also travelled to Ghana in the mid-1960s to learn from the country’s experiences in navigating a third path between socialism and capitalism, between the Communist East and the democratic first world. All four African-American leaders thus symbolize the common aspirations of people of color in America and Africa.

Director Shirikiana Aina accepting the Grand Nile Prize for Best Long Documentary at the 2017 Luxor African Film Festival

In 1966 Ghana’s national dream came to an end when the CIA helped stage a coup against the Nkrumah government, because his policies were intolerable to American Cold War interests. Industries Nkrumah had nationalized were re-privatized, and African-American intellectuals, like Angelou, were deported as threats to the government. Aina cites Awooner who argues that the overthrow of Nkrumah must be linked to other Pan-Africanists murdered or overthrown by the forces of reaction: Patrick Lumumba (Congo), Amilcar Cabral (Guinea-Bissau), Edwardo Mondlane (Mozambique), Modibo Keita (Mali), Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr.

Footprints to Pan-Africanism is available online from the Sankofa Bookstore and includes Brick by Brick as a bonus short.

< Back to the Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation