As a European-American male who grew up in suburban Chicago and Germany (teenage years), my knowledge of Native Americans in this country was wholly based on Hollywood Western stereotypes and a reading of 19th century authors James Fenimore Cooper and Karl May, both of whom at best propagated a “noble savage” vision of America’s indigenous people. And while, as a Boy Scout, I joined an Indian dancing group for about a year in 6th grade (a group without any Native Americans in it), the reality of life on and off the reservation was as real to me as life on Mars. Indeed, as numerous Native American studies commentators have noted, our society had made American Indians invisible, as if extinct. My own perspective has thoroughly changed in the last 18 months though, since the Archive began planning our series, “Through Indian Eyes: Native American Cinema,” opening at the Billy Wilder Theater on October 4.

I first thought about doing an exhibition on Native American stereotypes a little more than 10 years ago, when I was at the Hollywood Entertainment Museum, and I even attended a pow wow in Los Angeles to educate myself, but the time was not yet right. Then, approximately two years ago, the Archive was approached by UCLA graduate and prominent filmmaker, Valerie Red-Horse Mohl, who wanted to bring together UCLA-trained Native American directors for a film screening. We seized the opportunity and asked her and her colleague, Dawn Jackson, L.A. Indian Commissioner, to join a curatorial committee consisting of myself, Shannon Kelley and Paul Malcolm, our film programmers. Our goal was to present a major retrospective of films made by Native Americans.

As with every programming initiative, we began with fundraising, since the Archive’s budget for film series is almost wholly dependent on outside monies (apart from what we can earn at the box office). We approached numerous Native American tribal councils, as well as private and government foundations, achieving some success in both sectors, with a couple of grants still outstanding, and enough funds to proceed.

Meanwhile, the research phase began. We first put together as complete a list as possible of Native American film productions in the United States and Canada from the past 25 years, initially making the curatorial decision to not include Native films from Latin America or the South Pacific, as other indigenous film festivals have done. Utilizing sources like the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian website, which lists every film screened there since 1995, as well as Sundance catalogs, we identified hundreds of films which were directed by Native Americans. Over the past year, I personally screened close to 100 films, including fiction features, documentaries, educational shorts and animation.

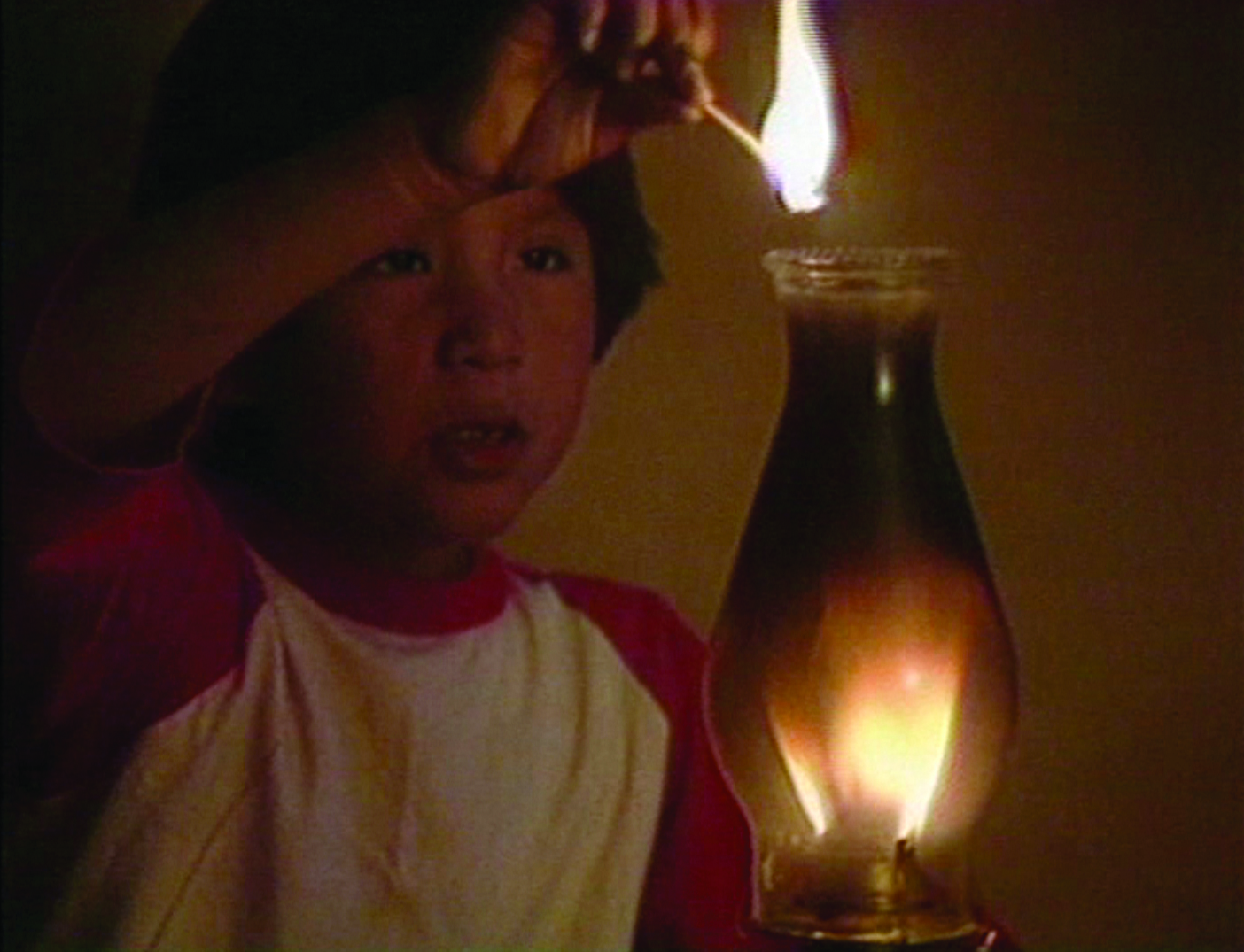

In making our selection for the final retrospective program, which will include as many as 60 shorts and features, and run from October through December, we hoped to present a broad representation of work from the past 25 years with a brief excursion into the earlier 20th century. We also wanted to present a cross-section of genres, as well as to represent the many indigenous nations that have taken the power of media into their own hands. Our series will include films by Inuit, Comanche, Hopi, Navajo, Choctaw, Cree, Cheyenne, Cherokee, Seminole, Creek, Mohawk and Pomo peoples, among others.

We hoped to present a broad representation of work from the past 25 years ... We also wanted to present a cross-section of genres, as well as to represent the many indigenous nations that have taken the power of media into their own hands.

While the films themselves have been a revelation, my understanding of these films has also benefitted from the growing literature on Native American cinema, including Jacquelyn Kilpatrick’s Celluloid Indians: Native Americans and Film (1999), Beverly R. Singer’s Wiping the War Paint off the Lens: Native American Film and Video (2001), M. Elise Marubbio and Eric L. Buffalohead’s anthology, Native Americans on Film: Conversations, Teaching, and Theory (2013), Michelle H. Raheja’s Reservation Reelism: Redfacing, Visual Sovereignty, and Representations of Native Americans in Film (2011),and Lee Schweninger’s Imagic Moments: Indigenous North American Film (2013). The recent publication dates for this literature alone indicate that our series is an idea whose time has come.

In putting the program together, we've learned a number of important lessons. First, the concept of a Native American cinema is and always will be an artificial construct, given the fact that cultural differences between members of different tribes can be as great as between non-Native and Native peoples. That fact notwithstanding, a Native American film aesthetic does seem to have been developing over the past 25 years: different ways of perceiving space and time, stories that are circular rather than linear, landscapes which are both real and allegorical. Thirdly, indigenous people may make films for themselves and their own people, not necessarily for Western eyes, with only a portion having ambitions to enter mainstream media production. Fourthly, as a non-Native viewer and English speaker, I will always only be privy to some of the messages and meanings inherent in Native American cinema, while local tribal audiences may read the work in completely different ways. Indeed, as Michelle H. Raheja argues, even a film like Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North (1922), which carries with it all the ethnographic biases of its Caucasian male maker, has been treasured by Inuit audiences for generations, because it is a real document of their ancestors. Finally, the work must be understood as an act of sovereignty against the backdrop of more than a century of racist Hollywood imagery---“talking back” and declaring their independence.

In putting the program together, we've learned a number of important lessons. First, the concept of a Native American cinema is and always will be an artificial construct, given the fact that cultural differences between members of different tribes can be as great as between non-Native and Native peoples. That fact notwithstanding, a Native American film aesthetic does seem to have been developing over the past 25 years: different ways of perceiving space and time, stories that are circular rather than linear, landscapes which are both real and allegorical. Thirdly, indigenous people may make films for themselves and their own people, not necessarily for Western eyes, with only a portion having ambitions to enter mainstream media production. Fourthly, as a non-Native viewer and English speaker, I will always only be privy to some of the messages and meanings inherent in Native American cinema, while local tribal audiences may read the work in completely different ways. Indeed, as Michelle H. Raheja argues, even a film like Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North (1922), which carries with it all the ethnographic biases of its Caucasian male maker, has been treasured by Inuit audiences for generations, because it is a real document of their ancestors. Finally, the work must be understood as an act of sovereignty against the backdrop of more than a century of racist Hollywood imagery---“talking back” and declaring their independence.

If our audiences can begin to see this work “through Indian eyes,” then we have done our job.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation

Comments